|

It's the Spring 2022 collection! Can you hear to pop-pop-popping of the cameras? Live from the Would-Be Farm, I give you...a fashion show of sorts. They prowl the stage. They have cheekbones to die for. Some trot. Or caper. Others preen and strut. Some amble, even. Many –– so many! –– are ready for their close-up, Mr. deMille.  Please disregard the off dates on these game-camera photos. The tiny chip's worth of brains that power the camera occasionally lose track. Reminding me, uselessly, of the first rule of time travel: ascertain your temporal location.

2 Comments

It seems like only yesterday: those exciting the first couple of months as landowners trying –– without success or joy –– to imagine staying in a tent at the Would-Be Farm. Even for a few days at a time, it's just too much cooking and cold wind, early sunsets and muddy boots. In the spring of 2014, we found a used camper at the back of an RV lot. We drove the 1985 Sportsman (so much orange plaid!) away for $800 bucks, hoping it would make the trip to my sister's lawn. A few solid days of rehab, a whitewashing, and voilá! a place to sleep, cook, and close the bathroom door. Bringing the Sportsman over to the farm was like the first part of a buddhist koan for capitalists: If a camper breaks apart on the twisty road, how attached are we to this material item? We were not tested. It held together even over those bumps and muddy ruts. We docked the camper on a bluff overlooking the marshy stream, the old barn foundation, and the antique windmill. Base Camp. It became almost immediately clear that Base Camp was by nature slightly too porous and fragile to stay intact in the North Country. The tin-foil roof leaked and some important wooden structure was spongy. We had visions of a foot or two of snow rendering Base Camp into a compacted oblong of foam and tin. That autumn, we rustled up carpentry talent in the form of Jeff's brother John, my sister Sarah, and Sarah's friend Curt Dundon and had them put our muscle to work constructing a shed roof over Base Camp. My sweet elderly Boston Terrier, Lilly, was there in her usual supervisory position. To this day, her ratty little footprints can be seen on the clear roof panels of the shed. Over the years, we slept like neatly stacked logs in our small bed in Base Camp. We drank innumerable cups of scalding hot tea and watched the weather come up the valley from a drafty inside. We berthed houseguests under the dining banquet. We saw deer and coyotes and turkeys wander by. Base camp grew more porous, though while mice found portals, raccoons did not. Then came the morning when the thermometer outside read 28° F. The inside thermometer, likewise, read 28 big degrees Fahrenheit. From my cozy nest of wool and goosedown, I said to my favorite skipper, "I don't know what else it's going to be, but the cabin starts with a wood stove." We finished the interior of the cabin during that first plague summer of 2020, channeling anxiety into planks and nails and paint. Through 2021, we kept Base Camp intact for houseguests, but perhaps we revealed her mousy shortcomings a bit too liberally; only one set of visitors moved in for a weekend. Other guests made themselves comfy on the expanded level parking area with access to shore-power. In any case, April of 2022 was time to play taps and send Base Camp along her dharmic way. We unbuilt the shed a little, which is to say, Jeff defied gravity and removed beams as well as yanking the A/C unit off the top of the camper and then, once the camper cleared the beams, replacing the beams AND the A/C. Not thinking, I charged into the camper to retrieve the fire-extinguisher and a box of potting gear while he was tap-dancing on the roof. One could nearly see the imprint of his boot in the vinyl-covered ceiling. We dug a pair of trenches for the wheels –– to keep the profile low, and ended up deflating the rear pair of tires (stale air!). The fact that all four tires held air is remarkable; the tires had to be 20 years old, and the porcupines failed to nibble on them. We first tugged and then pushed with the tractor and astonishingly enough, Base Camp submitted to being heaved onto the driveway. The next morning, hitching the truck up, we relived the koan: what if the hubs seize up or an axel gives out? what if the trailer's back breaks or the hitch lets go and Base Camp goes sailing into a ditch? "It's just as easy to call for a tow truck from the side of the road as it is to get them to find us here," we consoled ourselves. Our better helmsman took the wheel and, sticking to backroads and driving 45 (sorry speedy little car! sorry guy! sorry big pickup! sorry beat-up Suburu! sorry to you too!) we winced over potholes and gritted our teeth when the suspension rattled. And in about 30 minutes, the truck eased Base Camp into the muddy parking lot of the one salvage yard that scraps campers. I felt a pang, seeing Base Camp among the wrecks, but that big wheel of dharma will keep turning. So let us charge our glasses and offer a toast to Base Camp: the best $800 house of all time. This may –– or may not –– be your final resting ground. I suspect you have another season of shelter for humans as well as small rodents in your diminutive chassis. Hail Base Camp! Fair winds to ye! As for the shed, we have plans to transform it into a barn over the summer. A red one, as befits a farm.

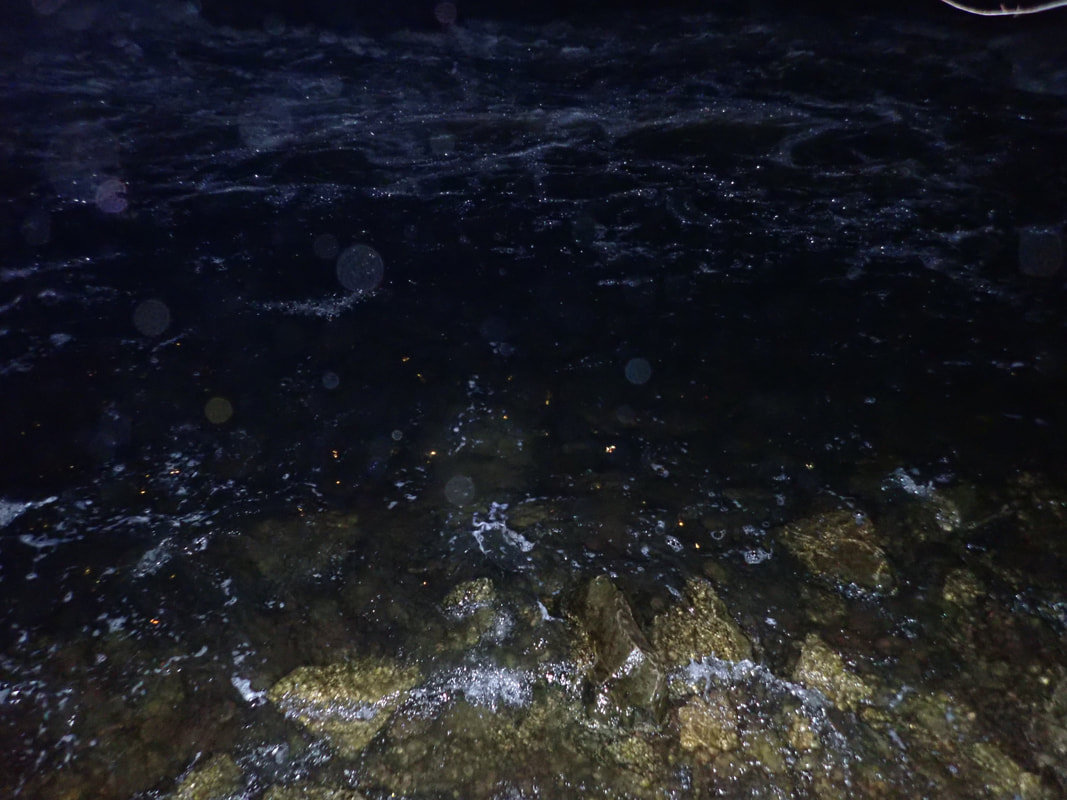

Every spot on this sweet blue globe of ours has its miracles: bioluminescent dolphins speeding under a sailboat on a calm night in the Gulf of Mexico like constellations on the move, the sound of peepers demanding the return of Persephone from the underworld, the scent of actual chestnuts roasting on an open fire. They happen all the time, but we only sometimes notice. For several years, neighbors at the Would-Be Farm regale us with the walleye run. Early in the spring, the story goes, northern walleye gather to spawn. The walleye –– Sander virtreus –– is a nice little freshwater fish, delicious and sporting to catch, a beefy cousin in the perch family. "You look for their big googley eyes at night," we heard. It's a natural wonder. It usually happens too early in the season for Mr. Linton and me. We miss maple season. We miss ice fishing, and generally, we miss the walleye. But not this year. Spring is dawdling, despite the peepers' chorus. We are here early. Our first nightfall, we bee-lined from the Would-Be Farm to the rapids of the Indian River. Flashlights revealed ambiguous tan shapes for a moment until our eyes reconciled the truth: those are fish, and those are indeed big glowing googley eyes, as promised. But in such astonishing volume. SO many fish. At the flash of my camera, each googley eye showed as a spangle –– a spark –– a star –– in the madly rushing water.

There's no flinging about like salmon, no crazy aggression, just this seething vision of piscatorial mass. We stood by the roar of the river (the waterfalls are just out of frame in these photos, cold and brutal in the dark) for a long while, meeting their googley gazes under the cloudless starry night. Then, shivering, we chased the beams of our flashlights back to the truck. On the far edge of the parking area, the game warden eyed us but didn't bother getting out of the truck. The locals have been known to fill their wading boots with walleye and then squelch right past the officer, equal parts insouciant and insolent. But Mr. Linton and I might have been wearing big mouse ears. Obviously tourists. Just here to see the sights and move on.

In 2015, I stuck a couple of pear trees into the ground without knowing my land very well. As it happens, the soil is thin just there, with bedrock only a short root away. And the wind whistles up and over the little bluff. I imagine it's as bitterly cold a spot in the winter as any I could have found had I been looking for it.

At the end of the summer of 2020, I decided I'd probably cull them come spring. So much of farming is editing, come to think of it: tearing things out and moving them around or having to put them into the discard pile. Sigh. I didn't say anything to the trees –– after all, winter does a lot of my hatchet-work for me. Come spring, however, I pushed a shovel into the dirt around the littler of the two, apologizing as I tussled it from its shallow home. I held the truncated rootball in my hand for a long moment next to the neighboring pear tree. "Look, buddy," I told the tree. "I don't enjoy doing this. I'm going to give you another summer. Think about it, okay?"

After some thought, we decided against doing our own concrete work. The guys managed to dig, gravel, and move the concrete by wheelbarrow from where the 'rete truck backed into Jeff's velvet field of green in a single day. (PS, it took us only a week or so to fill those ruts and overseed the area with clover. The scars on the field are nearly invisible.

So steps.

I meant to just put a couple of flagstones into the ground, but then the stones started piping up and the hill was asking for more... The Would-Be Farm has had a wet 2021 summer. The grass grows like weeds. The weeds grow even faster. But the flowers have been pretty glorious, honestly. Last year, my long-suffering sister agreed to start some of my eccentric seed choices. In March, when gardeners in the North Country begin to stare longingly at anything green in hopes that it might be alive, grow-table real estate is valuable. It was a generous offer. So I sent packets of ground cherry seeds, monarda seeds, borage seeds with my hope. The ground cherries refused en mass to start, and the borage, once started, too closely resembled a weed and in June was twice accidentally whacked and gave in to entropy without fuss. But monarda –– monarda was the standout: each seed sprouted and refused to be cowed by last summer's drought. Back in April in that first plague year, under the grow-lights, my sister sister looked at the monarda starts with suspicion. "Are these," she asked me dubiously, "bee-balm?" Me, consulting the inter webs: Um, yes. No wonder these seeds had sprouted: the stuff had taken over a whole corner of her flower-garden. I could have as much as I like yanked out of her garden. For crying out loud. Sure enough. Those wee four-leafed starters from last year turned into thigh-high big bursts of vivid color: clear red, pink, deep fuschia. The scent is a bit like oregano, strong and –– allegedly –– unappealing to some of the hungry natives of the Would-Be. I don't know if deer and rabbits and porcupine and woodchucks and all will continue to avoid the plantings. It's all one big experiment. I've put tasty fruit trees in the midst of all that color, hiding them among the strong scent and bright color until they are tall enough to avoid the predators themselves. Meanwhile, call them bee balm or Monarda, them what you will, the flowerbeds are hugely popular with the pollinators We'll see if they take over the orchard. We'll see if they protect fruit trees. Knock wood, we'll see.

For a couple of months when I was in fifth grade, one of the neighboring horses escaped its field. Even then, the neatly fenced landscape of small dairy farms was sliding away from cultivation. It was possible for a large hoofed mammal like a runaway horse to make itself scarce amidst the uncut brush. It set my imagination on fire. * To break the rational universe, yes, the happiest of all combinations in the English language would be the impossible pairing of "free" + "ponies." But don't be a fool, man, the space-time continuum can't bear the strain...

Lucky reader, we have NOT world enough or time. But as my skipper recently remarked, "You can take the girl away from the horses, but you can't take the horse out of the girl. We were heading down to the river to do some paddling and fishing, four of us convoying our kayaks along a remote stretch of private dirt road when, like a big blue bird of happiness finally coming home to roost, abracadabra! A pony! As someone in a dream, I fed my prize a nibble of apple and rubbed her ears. I whipped up a serviceable halter from the bow line of my sister's kayak and dropped it over the pony's head and commenced the long walk to the Would-Be Farm. My fishing companions had a variety of reactions. The retired state cop, visibly relieved at someone taking action, drove off saying he'd phone in the missing pony. My sister echoed my exclamations of "A PONY!" and took photos. My sweet spouse suggested that I didn't need to move the animal anywhere. He left the second half of the sentence, "let alone bring it home" unspoken.

Do I need mention that it began to rain? Or that, once at the Would-Be Farm, the pony ate a snack of grits, drank a bucket of water, took a vigorous roll on the newly cut grass, and trotted off in the direction of the wild back half of the Farm. The first rule of farming? Right after "If you have livestock, you'll have dead stock," is "Fences first." There is no comfortable spot to stow a beast of burden at present at the Farm. I found a longer bit of line and made a more secure halter, and when the pony trotted back –– and toward the road –– I recaptured her. Making sure she was familiar to the limits of being tied (she had showed a great deal of sensibility and calm on our long walk), I anchored her to a handy tree and ate a belated lunch. The consequences of my actions tossed her sweet head and snorted impatiently. She got a hoof over the line and stood balanced on three until I put down my lunch and rescued her.

She snorted and backed with zero dignity into the tenting platform so that she could rub her butt against the edge of the deck. She took a bite of the evergreen and theatrically rejected it, tossing her thick mane and blowing flecks of green around. She was bored, bored, bored! It entertaining program, but not a sustainable one. I laid the options out to my favorite skipper: "One of us will have to drive up the road and ask a neighbor with a corral if we can put the pony there. The other will have to stay and hold the pony's lead." Into the considering silence, I added, "Which one do you want least?" He elected to hold the pony. The man surprises me. I gave him a pointer or two –– he generally dislikes the whole family of Equus –– and dashed off. Luckily, there's a messy farmstead up the way with a handful of cattle and horses, plus chickens, and as it turned out, eight sheepdogs. Beware the dogs indeed. Standing on the running board, I asked the woman who emerged from the scrum of dogs, "Hey, have you by chance lost a pony?" She was standing a couple of yards away from the fence inside which a variety of horses and ponies and cows were calmly eating hay. She gestured over her shoulder and said, "Honestly, I don't know. These are my husband's horses." I thought: and THERE is a successful marriage. I told her about my wild pony, and she said, "Hmmm, my father-in-law lost a pony last summer." (The youthful horse-crazy kid in me silently fist-pumped at this additional proof that wild pony herds are possible). Then she said she'd better come take a picture and text it in case it was one of her father-in-law's. Yes. It was one of the father-in-law's bunch of horses, she told me. Name of Daisy. "She's a wanderer," my neighbor said, "Though usually she stays on the other side of the river. It's a long way to walk." We chatted a bit, and then my neighbor led Daisy away. "I'll bring the rope back," she said. I sighed and then said to Mr. Linton, "So, you remember that time we went fishing and I caught a wild pony?" Oh glory! Back in 2019, my sweet mother-in-law Pat and I spent a delightful weekend planting jonquil bulbs.

*Little known fact: Squirrels cherish lofty landscape architecture ambitions. Unsupported by taste or formal learning, but marked by passion and energy. And then the waiting begins. A winter passes. The first spring arrives, and the bulbs do their job, transforming stored potential energy into cheer. Any chunky little bit of starch can tide a body through a season. No judgement. We've all been there. Anyhow, the real test of the bulb comes after a full year. Has the little bulb put down roots? Have the squirrels decided to remodel the bed of flowers? So this spring? Hurrah. The bulbs have mostly flourished, putting up multiple stalks and lovely flowers.

In the nature of gardening nature, however, I find myself perusing those colorful catalogues for just a feeeeew more. Like everybody's Uncle Ernie, I bring you... a slide show. By our unscientific counting, we are guessing that we have more bobcat and fewer coyote snaps than usual. Only the one bear, but honestly, who needs more than the one? Plus, my personal weakness: a nice-looking free-range peep.

As a green lass, I also read A.E. Housman's The Loveliest of Trees. It's got the virtue of being short to balance against its general gloom and the inherent math problem of "threescore and ten." For those of us who don't calculate in base score, "threescore and ten" means 70, the average span of human life. His point is that 50 springs is not enough, no matter how you slice it. Preach it, brother.

I've over-ordered spring plantings, I've pack-ratted a mound of supplies, and as soon as I manage my second vaccination shot, we are heading to the Would-Be Farm. Because it's April. Already! |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed