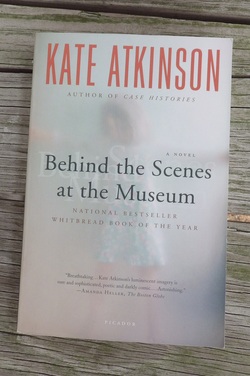

Or double-click and download this book. Right now. Seriously. Still reading my blog? Thank you, and no, this is not my pen name. Still here? Bless your heart! Okay, I can understand doubt and resistance. Let me blab a little about Behind the Scenes at the Museum by Kate Atkinson. I've been disappointed by some of the prize winners out of the UK (Not naming names, but the Booker Prize, "the best original full-length novel in the English language" has me scratching my head on a regular basis). But this one --! Kate Atkinson's debut novel, Behind the Scenes at the Museum, won the Whitbread (now Costa Award) in 1995. I regret not having found this one sooner, because she is a wonderful writer (she has a compelling mystery series featuring Jackson Brodie including the lovely title Started Early, Took My Dog) and this a great story. The novel starts: "I exist! I am conceived to the chimes of midnight on the clock on the mantelpiece in the room across the hall. The clock once belonged to my great-grandmother (a woman called Alice) and its tired chime counts me into the world." And continues as the narrator, Ruby, is born ("I don't like this. I don't like this one little bit. Get me out of here somebody, quick! My frail little skeleton is being crushed like a thin-shelled walnut.") into 1952 York, in the north of England. The family -- unhappily married George and Bunty, Ruby's sisters, a grandmother -- lives above their pet shop. Each is wrapped in his and her own concerns, which are carefully observed by Ruby in a way that is by turns laugh-out-loud funny and breathtakingly sad. The storytelling seems like magic: "Tom, however, continued to believe that Lawrence had been spirited away into thin air, infecting the younger children with the idea so that for ever afterwards when they remembered Lawrence they remembered him as a mystery, for they never heard from him again, although he did try to write but the family had moved on by then." Ruby tumbles over and then circles a handful of family secrets. The secrets are neither spectacular nor sordid, but they resonate and amplify forward and backward into the past of the family. Yeah, I know, I make it sound...not so spectacular. But believe me when I say get your nose into this book. And then don't plan to get anything done until you've finished. You're welcome. In advance.

0 Comments

I am not the only one looking for answers. Here's a trio of musical offerings on the subject of ignorance (and bliss?). From South Africa, Ireland, and Britain... The Arctic Monkeys are good for some existential doubt, plus of course some trippy graphics.  In Polish, the phrase is pronounced (as I hear it) "Nemoy seerick, nee molya mahlpey." It's a nice piece of distancing humor, unless of course, these ARE your monkeys, and it IS your circus. I grant you, two elderly small dogs do not much of a circus make. There's no trapeze, no elephants, no big top. But we have spangles, clowning, a variety of death-defying feats, and they do present a startling spectacle when leashed and walking.* Have we acquired another diminutive retread for the household menagerie? Not in this decade. This well-groomed poodle is another eccentric old tenant at Uncle Markie's Home for Wayward Pups. A bit of a howler when left alone, she kept Lilly company while Markie was away recently.  (*The word "walking" is not quite adequate to the occasion. "Walking" sounds so linear -- as if we start and go someplace with purpose. The process is more like a swooping, circling Spirograph of dog movement around a ringmaster. Passing cars pause at the sight of a human-and-dog dust-devil in slow-motion. Pedestrians nudge one another and smile at the show.) The old lady-dogs maintain cool diplomatic relations, despite sharing a distaste for the vacuum-cleaner and a fondness for the dog-bed. Whether they like to admit it or not, they both huff down their kibble with more gusto for having a bit of encouragement and competition. But they are not close. The poodle seems as insubstantial as a puff of goosedown next to the solid brick of cheddar that is the resident small dog. Though she is younger, the poodle seems older, drifting around on tiptoe and staying out from underfoot. Still, it would be only a tiny stretch to have the poodle sport a tutu and jump through hoops in the center ring. Lilly is more of a roustabout by nature, hauling on ropes and shouting at the rubes. She does not have the figure for prancing around in a leotard.

I snapped this photo offhandedly, thinking, ooh, spooky statue looming over some flowers -- doesn't he just look like a ghost? My attention was on the Arc de Triomphe, a speck in the distance, whither I was hauling my traveling companion on our blitzkrieg tour of Paris. Later, I wondered who in the world this bronze guy was meant to be*. One of the many reasons to rejoice in having survived until this point in human history: this website here, which lists all the sculptures that can be found on the streets and public gardens of the City of Light. Sorted and searchable by area, by subject, by artist, et cetera. With links. I know, I know -- the internet offers so many surprises and pleasant diversions, but Jupiter! A listing of public art for a whole city? A really complete listing? Because, as the site explains, unhappily (perhaps my favorite word in French: "malheuresement"), visitors and passers-by might not know the names and artists of the many many pieces of art that grace the streets of Paris. That's just crazy cool. Nerdy amazing. In a different decade, I'd have to give up the idea of identifying it until a return trip. If I could find it again. If I went again. If it were labeled. *The sculpture is called "Hommage à Georges Pompidou." It's in Les jardins de Champs Elysées and was made by Louis Derbré in 1985. Pompidou was of course a former president of France, and I stand by my initial assessment of the sculpture. He looks a little spooky.  It's the first question people ask about our newfound apple trees: "Yes, but what KIND of apples?" There are, after all, thousands of varieties ranging from common MacIntoshes and Granny Smiths to mysterious and rare Black Oxfords or Roxbury Russets. What kind do we have on the would-be farm? Short answer: we don't know yet. We could go all CSI and send samples to the lab for genetic testing. But honestly, that would mean separating ourselves from a chunk of change to discover -- what? That we have a fussy Yellow Moon, three Pink Ladies, seventeen Romes? Which will become clear (knock wood the weather cooperates) in the fullness of a growing season or two. A bit of observation can reveal so much. As my Cornell farming classes have emphasized, the secret to agricultural success is in the detailed records-keeping. So we'll be tracking each individual tree. Because there are 100 or so individual trees growing wildly on the would-be farm, the process starts with differentiating every tree from its neighbor. I'm reluctant to purchase tags from the nursery supply stores. Honest to pete -- a fluttering set of plastic twist-ties? Flimsy.

Aluminum cans -- not recyclable by the dint of solid lobbying here in Florida -- yield a neat and gratifying tag when snipped and folded into shape and then incised with an identifying number. Paired with the judicious use of a spreadsheet, these tags are the the start of keeping track of the growth habit, health, blossom production, and fruiting tendencies of each tree. (I know, I know -- the excitement is palpable around here!) Of course, a would-be farmer can dream: maybe a long-lost heritage fruit will be hidden in our neglected orchard. It's not quite a movement, but there are people in search of forgotten treasures like this. No matter what kind of trees they turn out to be, I look forward to being able to say, "Oh, yes, we have Romes and Macs." Or maybe, "Why yes, we also have a few Pink Ladies and Blue Permains." Or even, "Oh, you need to try the Pitmaston Pineapples and Prairie Spies -- we didn't even know we had 'em until the third year!"

They're called "coydogs," though strictly speaking, they aren't. Only rarely does the offspring of a dog and a coyote survive in the wild. Still, these coyotes howling in the night (listen to #45 in this link!) in northern New York State look bigger and tougher than the skinny coyotes of the wild west -- probably because they have quite a few wolves in their family tree. It's not a new story. When Eastern wolves became thin on the ground in the North East US in the last century or so, they did what we all do when the dating pool gets shallow: we widen the search. Change our expectations. Try new things. "Coywolf" doesn't sound nearly as cool as "coydog," but evidently, it's the more appropriate terminology. But enough about wild canid dating. It's worked well enough to bring a sizable predator into the niche that wolves used to fill. Coyotes have come to the North Country in a big way, bringing with them fear and loathing. Coyotes are predators. They devour other animals for a living*. It's not pretty: they will eat newborn calves, deer, rabbits, cats, sheep, chickens, small dogs. And it's human nature to resent this kind of thing. I can't really blame people who have lost livestock or pets to take revenge in bullets and poison. It's how we humans got to the top of the heap. Yet -- at dusk, watching a single coyote through the telephoto lens as it hunts a mouse? Yes, a wiley, wild animal. Yes, potentially dangerous. Those fangs! But really -- this coyote trotted out into a hayfield overlooking a TILT preserve as the light faded one May evening, ignoring the cattle in favor of something small and elusive in the tall grass. S/he is eating a mouse. What could be more homey and appealing? (*Coyotes are technically omnivores. According to scat analysis, they eat just about everything, from garden veggies to berries and fruits, grasshoppers, porcupines, and they scavenge already-dead carcasses. Bless their hungry hearts.)  It's not exactly unique. At some point during the day, you find yourself standing in a room looking around with a certain sense of urgency. You may think, "What did I come in here for?" Or maybe, "What was I going to do?" Perhaps you mentally tick through a list of the errands or chores that might have sent you into this room at this moment. Sometimes you draw a blank. It happens to Lilly. Especially as her hearing has grown -- ahem -- less acute, I sometimes find her frozen in place, as if cast adrift in the back bedroom. I haven't been able to watch very long -- her determined little form plucks at my tenderized heartstrings. I clap or call her name, or stomp to get her attention, and she turns with an expression of relief so sincere that it's with difficulty that I resist the temptation to pick her up and squeeze her. She is an elderly dog, after all, and has never enjoyed being separated from the solid ground, regardless of my little firestorms of affection.  My mother was good with wild creatures. She took in injured birds -- including those delivered by the local game warden -- and cared for them them until they were healthy again or could be turned over to qualified vet care. Which is why, for at least some chunk of time in my childhood, it was not surprising to find whole mice frozen solid and Saran-wrapped in the freezer. Or moles. Sometimes, opening the cold cave of the Frigidaire, a girl could come nose-to-nose with a furry dead rabbit donated by a passing hunter. Most often, when a hunter appeared at our door, it was to borrow the dog (an excellent retriever) for a day of duck- or goose-hunting. But sometimes, it would be a gift instead: a wounded bird of prey or a brace of dead rodents for whatever raptor was already convalescing at our house. Once, while Daddo slapped together an appropriate box, a wounded Snowy Owl strode angrily around the living room, clacking its beak in warning with a sound like a softball connecting with a hickory bat.  Another time, there was a winsome little Screech Owl who would lean into a petting for as long as anyone had patience to continue. A sparrow-hawk was among the first of those rescue birds I remember clearly. A fledgleling Falco sparverius was found huddled beside the road, and someone thought to bring it to Mumsie. It was not far from being able to fly, but the bird needed practice catching prey. Mumsie built a little set of jesses for it from a picture in a book about falconry, so that she could retrieve the bird after short flights. That sparrow-hawk's training as a tiny killer culminated when Mumsie staked out a live mouse for it -- a tiny noose around a tiny hind leg fastened to a nail driven into the dirt at the base of the bird's perch. After a brief, anticipatory pause, the bird stooped and mantled (as the falconers phrase it) over the rodent. In a very few moments, with only a few faint sounds, all that was left was the little loop at the end of the string and a happy bird ready to go into the wide world.

And of course my sister and me looking at one another across the bird's head with a complicated mixture of reactions. So many of these childhood adventures seem to end -- in my memory anyhow -- with my sister and me looking at one another: both astonished and jaded, at the same time witnessing and disbelieving, and knowing that we will be telling this story one day. |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed