|

Some things I have learned about growing mushrooms: fungi digest their meals before ingesting them. Freaky deaky. It goes like this: fungus grows in a colony. A colony (the parts you don't see, usually) sends out cells that figure out what's for dinner. The fungus produces the appropriate enzymes and sweats these compounds into their general area. Complicated carbohydrates (wood, leaf-litter, manure, coffee grounds, old clothes) get broken into smaller components and then yum-yum-yum, the non-plant absorbs basic building blocks of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and so forth, transforming material into delicious meals for themselves. Most of this happens under the surface of stuff. When a log gets punky and papery, for instance, it's probably because fungi has colonized and mostly digested the good stuff from it. The part of the fungi that we do see? The odd grey growths on the sides of dead trees, the circles of orange toadstools, the package of vaguely phallic objects in the produce section of a grocery store? These caps and stems are the final stage of growth for some fungi. When fungi produce mushrooms, it's called "fruiting." And such fruit!

Varieties are blue or tan or yellow, tiiineensie or largo, spiky or smooth. Something edible for everyone: Shiitake, oyster mushrooms, portobellos, truffles, morels, hen-of-the-woods, maitake, lion's mane, nameko, blewit, wood-ear, enoki, blacktop, shaggy mane, tiger sawgill, scaly lentinus, hairy panus, turkey tail, king stropharia, parasol, elm oyster, the choices are legion. Me, I am not a fan. As my mother said of meatloaf: "Everyone has her own recipe, but it all tastes the same." Still, other people enjoy mushrooms. They buy them and everything. And as it happens, mushrooms might be another one of the crops that might thrive without a constant gardener looking after it. So that's part of our new neural pathway this spring at the Would-Be Farm: mushroom cultivation. I look forward to reporting details when we've accomplished something.

4 Comments

Maybe it's perhaps a genetic predisposition that makes a person lean toward word-playful, irony-appreciating deep-voiced performers. John Gorka, dude. Leonard Cohen. Richard Shindell. Jeesh. Talk about Wonderbread white. But alas. Perhaps it started with the environment. For me, those long, looooong school-bus rides listening to dopey 1970's music on the radio. Thank you, Mrs. Gamble, by the way, you were a pretty cool bus-driver. I only wish I could erase Wildfire from my inner jukebox. With that said, when this came on the NPR Tiny Desk Concert, I was captivated. On the third listen, I browsed what passes for the liner notes and realized of course. This is the same guy I wanted to hear when he was the lead singer for The National. Sigh. Short on time? Skip to the area of 8:45 for "Need a Friend." It's amazing how over-produced their album sounds on this particular tune. My favorite skipper, however, not a fan. Hmmm. He favors the B-52's and the Doors and rarely accepts a substitute.

Side-note: I categorically deny ANY interest in hearing even one more thoughtful/sensitive singer-songwriter with three names. That third name seems to break the bass spell.

Wholesale domestication started around 11,000 years ago, according to the latest thinking. 11,000 years ago is only a few generations after plant farming had begun. Taming various wild prey animals -- sheep, bees, duck, goats, guinea pigs, llama, cattle –– could not have been easy; go face down a white goose or a tom turkey and then let's talk about, say, a water buffalo.

I'm not exaggerating. The first cows in Europe, aurochs? Seriously, the stuff of nightmares: 1500 lbs of leggy temper, six feet tall at the shoulder and a horn-span of up to seven feet. Categorically NOT tame. The last specimen of the species lived until 1627 in the forests of Poland. She died in the interest of steak, not so surprisingly. I just wonder at the gall of the first person to put a thieving hand upon the hairy udder of a wild cow. What could possess a person to try? A dare, maybe? Or maybe impelled by a rescue effort –– a calf or a human baby who needed that milk enough to risk the effort? Some dramatic extremity, no doubt. Unnatural selection has led from these wild and wooly forebears come the sweet-tempered Jerseys and Gurnseys, and those homey black-and-white gold standards of milk production –– Holsteins. Me? No, I don't want another cow in my life. I know the ways of young Holsteins from many a winter's day dealing with scours in a veal calf. And there was a year or so when my mother and I swapped the care of a hairy herd of Highland cows for the rent of an old farmhouse. Small cattle, Highland cows, but feisty. Anyway, enough cattle for my lifetime. Maybe. But goats, now, huh. Goats... The blog will be on hiatus for a bit while I attend to some foredeck work...

Flickr Photo Album from one of my favorite sailing photographers, Bill Clausen. To the sound of cheering crowds (modern-day crowds, that is –– the noise a swellign crescendo of plasticky key clicks) Spawn of Frankenscot arrived safe and sound in Key Largo 1 day, 12 hours, and 46 minutes after starting the 2016 Everglades Challenge. They were the first boat to finish and they broke the previous monohull record by 12 hours. Click-click-click hurrah! Social media applauds! Here's a gorgeous short video of the team –– shot by Ninjee's cousin Simon Lew via helicopter over the Gulf of Mexico. They were fortunate in the conditions. The wind stayed mostly abeam or aft, so that they were running or reaching about 75% of the course, with only a few chunks of rowing against the tide (like at the Indian River Pass), and short slogs upwind with crew on the wire.

The Spawnsters barely had time to snack during the trip, though they wouldn't have starved: an unfortunate Spanish mackerel, leaping boisterously from the water somewhere out in the dark blue empty, landed with a surprising thud in the cockpit in the middle of Saturday night. The team trained their headlights onto the piscatorial visitor. "What is it and where should I grab it?" Moresailesed inquired before flinging it (by the least harmful corner of its tail) back into the sea. The mighty yacht herself landed with a thud from time to time in that last stretch of what navigators call "skinny water." Florida Bay (Rod Koch describes it as "lunar") is shallow and full of both mucky sand and hard coral. Said boat designer Ninjee, "I didn't realize how much running aground we would be doing." Discussion of a stainless-steel leading edge on the centerboard followed. Spawn disturbed at least one hazard of the course: a 7-foot-long shark had the startle of its weekend when the boat passed over it in about 2 feet of water. "It looked like an explosion of mud behind us," said TwoBeers.

Special thanks to Ensign RumsDown, who IS a driving Ninja and generous friend.

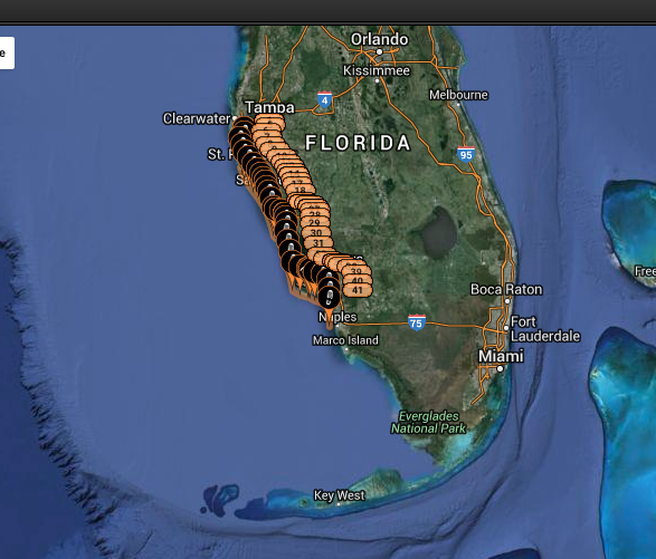

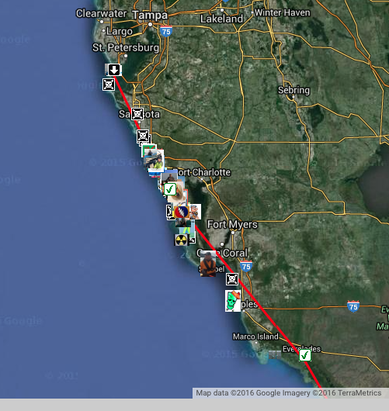

As he announced to the team in a manly bellow from the shore of Chockoloskee (after Mary and I had warbled "I love you" across the starry, echoing darkness) "I LIKE YOU!" Really do. In 2014, when my sweet husband competed in his first Everglades Challenge, it was nerve-wracking to try to follow his progress. Although the personal tracker (required by the competition's rules) was working, the device had a tendency to flip over and stop transmitting to its satellite. So the team would drop off the map for some chunks of time. This year, I am very happy to say the tracker is on track! A little modification to the deck is proving to work quite well -- the SPOT nestles into a recessed cup on the back deck, clipped into place. I post this 14 or so hours into the race, and while there are no other boats in their division (three-person team in a monohull), they are at the front of the pack. The WaterTribe site tracking map has been up and down, though here's a screenshot from a few minutes ago...Click on the map for the link. Keeping fingers crossed.

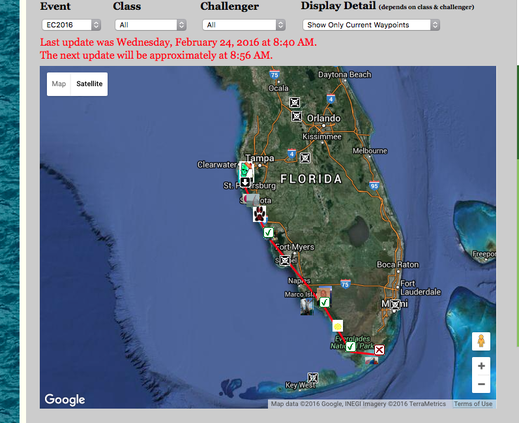

The WaterTribe website tries to provide a real-time map of the competitors' geographical locations. It has bogged down pretty readily in the past, but the link is here. Or click on the image of the map below. (Ain't technology grand?!) I know I will be hitting "refresh" at a slightly unhealthful rate while the fellas are away from land.

I'll try to update the team's progress on the Frankenscot Facebook page. Keep in mind that even as we shadow Spawn's track on shore, we will be in and out of cell/internet coverage, but the shoreside team (ERD, Bookworm, and Ms. Ninjee) will do our best. Good luck to all the WaterTribe!  When Spawn takes to the water this coming weekend, we can hope the creature does so in style. Oh, I'm not talking about crispy new sails or all those lovely electronics that had to be re-purchased after they failed their swim test in February. Nuh uh. I'm talking fashion. For instance, the bedazzling of Spawn. The nice UPS folks delivered a big fat roll of super reflective tape last week –– the kind favored by firefighters and highway road-signs –– which I have been slathering all over Spawn and her crew's gear...Ooooh, sparkly! A strip on the transom, check. A matched pair at the bow, check. Stripes at the mast-tip, boom end, and at neatly spaced intervals on the racks. Check, check check. Dots on the dry-suits, dots on the life-jackets, ovals on the trapeze harnesses. And of course, wide bands at the end of the oars. The phrase "lit up like a Christmas tree" drifts to mind.  And because it's not really a sports team without uniforms, there are Spawn shirts aplenty. While racing, the sailors will be wearing safety-orange long-sleeve sports shirts. Photos don't do justice to the racing shirt's DayGlo spectacularity. Think prison jumpsuits. Think highway construction workers. Think Bananarama! in 1985. Thanks to Carol at CDM Gifts who did the sublimation printing. (Sublimation printing is the process that allows for quick and permanent printing on polyester. Kind of amazing.) And why would I want polyester? In a word, sun protection. And thank you Leslie Fisher at Masthead Enterprises for connecting me with Carol! The Spawnsters each have a nifty embroidered ballcap from kindly supporter Ned J., who reads the blog from Maine when he can't be sailing in warmer climes. They are even personalized with our WaterTribe names! Thank you, Ned and Anne!

Unlike so many modern fashionistas, Team Spawn has free range of the snack aisle. They will have granola bars, breakfast shakes, hearty meat rolls, and homemade goodies like beef jerky and these cashew-dried-cherry dark chocolate bars. ...Assuming they remember to fuel the machines. All three are what dog-training professionals would call "Not food motivated." And in the four remaining days (Ah! Ah! Ahhhh!), Captain TwoBeers will be figuring out how to stow all this stuff.

Spawn might be ripe for a closet makeover. Is there an HGTV show with this as the topic? How first-worldy a problem is that? |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed