|

Life is not the only thing out there imitating art. Evidently Nature's in on it too. According to Edgar Degas, "Art is not what you see, but what you make others see." And for that I might as well go ahead and apologize. I was thinking about the Alexander Pope quote, which was –– I thought –– Art is but Nature to advantage dressed. Or, in this case, not dressed. I meant to rift extensively on part about being undressed. Low humor, sure, and possibly dragging in the topic of saggy pants.

But when I checked the quotation (From his Essay on Criticism, which is in strictest truth a poem), Pope actually wrote: "True wit is Nature to Advantage drest,/What oft was Thought, but ne'er so well Exprest,/Something, whose Truth convince'd at Sight we find,/That gives us back the Image of our Mind." Oh Alexander Pope, you navel-gazing noodler.

2 Comments

Goblin Valley is full of hoodoos –– those weirdly worn pillars of sandstone that resemble human figures. And I mean the valley is FULL of them. It was first called "Mushroom Valley" when Anglos first found it. Although in full disclosure, even more than goblins, I think one could argue a valley of phallus-like items. Names matter. I get it. Who in the world would agree to chaperone a busload of teenagers to Dingus Valley State Park for an overnight tenting adventure? But how about Ponker Valley? Pizzle Park? Tallywacker Trail? I can restrain myself only by strong effort. Goblins! Goblins! In any case, the valley opened as a state park in the 1964. It's one of the few parks where electric scooters are not prohibited on the roads, and where a visitor can meander at will up and over the sandstone structures. We put in our miles while visiting. We set off at dawn and returned to the Winnie reminded of how very dry and how very empty Utah can be.

I read Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey only after we'd hiked in Arches National park in July.

We started the Devil's Garden trail at 6:30 perhaps –– the sun was up, but the shadows were long when we left the paved trail at Landscape Arch. Bonus travel tip: Even in the busiest and most popular national parks, we found that by hiking a few hundred yards down nearly any trail*, we could leave most of the seething mass of vacationing humanity behind. Sad truth: few tourists do more than meander to overlook, snap a photo, and then roar off in an air-conditioned car. Edward Abbey was right: "What can I tell them? Sealed in their metallic shells like molluscs on wheels, how can I pry the people free? The auto as tin can, the park ranger as opener." Desert Solitaire p 290. *Exception to the trail rule? The Narrows at Zion. It was kind of the only game in town after the landslides of 2018 (aside from scaling bare rock faces). That hike –– a wet, awe-inspiring meander up the slot canyon –– did fill up considerably come lunchtime. Early morning or off-season recommended. So, back to the dusty devilly trail. Devil's Garden trail is nearly 8 miles there-and-back again. A good scramble up red sandstone rocks, along ledges, through dusty piñon pine groves. We ran into families of deer –– the females showing ribs and the fawns leggy and curious –– a couple of parties of human hikers, lizards of various stripe, intriguing tracks in the sand, and the odd path marker. Some markers odder than others. To a certain sort of thinker, this is an ambiguous sign: I read it first as a series of nouns: road + leaf + laundry. Clearly wrong. A series of verbs: follows + goes + cleans. Er, nope. Because, you know, why? But interesting. Return to this thought later, I told myself, tucking the camera back into my pocket. I stopped for a sip of water a hundred or two hundreds yards later. The words transposed themselves: Trail Wash Leaves. That seemed nearly probable: maybe the trail had a new name. The National Park people seem to engineer their signage so that visitors can have a more genuine park experience, complete with navigational anxiety and an understanding that maps are imperfect representations of the truth. Maybe. But probably not.

The pieces fitted together a half mile or more later: Alert, hikers: your trail, which has followed the path of this dried stream-bed –– known locally as a wash or a gulch –– is about to diverge from the stream-bed.

Oh. That. Huh. For the rest of the walk, series of words started presenting themselves. Triangular structures, each side a simple word that goes both ways: One can trail one's hand on the trail. One can leave the leaves behind, one can wash the wash. Stone Ride Ice. Rein Plant Saddle Mount Slide Hollow. Chant Riddle Stop. Then we arrived back at the start of the trail. And in the blink of an eye, we were addressing ourselves to pizza and cold beverages and a bookstore on the funky little main drag of Moab. During our 9000-mile trek around the western US, we learned a few things about Utah. First, it's got zillions of acres of dramatic desert scenery and otherworldly rock formations. One ranger-led evening program included an entertaining slide show where the audience was invited to guess: Mars? Or Utah? It was harder than you might expect. Second big thing about Utah? Mormonism. What we don't know about the religion would fill a library. (Just for the record: our ignorance extends to nearly all branches of belief. We are non-denominational like that.) But thanks to the Big Parks Trip, we do know why there are orchards at Capitol Reef National Park, and why the fort at Pipe Springs was built. Here's my abbreviated version of the history: Back in the day (mid 1800's), when Mormons were facing persecution in the eastern US, Brigham Young led his followers into the Utah Territory, where they could practice their religion without oversight or interference from the government. Since, naturally, the territory was not yet a state. Long story short, the conflict between faith and state came to actual war between Young's followers (the Nauvoo Legion) and the US Army.

As in, one can wander around in the orchard and eat apricots to one's heart's content. 3000 or so fruit trees are maintained by the National Parks Service (the last settlers moved out in the 1960's after selling their land to the Park). An earthly paradise. And likewise, the Mormon ranch at Pipe Springs is a National Monument. Halfway between Zion National Park and the Grand Canyon, Pipe Springs served as a stop-over for early tourists out west. My historical summary: For time immemorial, local Kaibab Paiute people came here on their annual circuit. At the end of winter, this little oasis was full of rice grass and small game. And for time immemorial, the Paiutes moved along for better hunting and gathering as the seasons changed.

Luckily for the Mormons, these particular natives were not a warlike lot. Between small-pox, TB, and starvation, the local population of natives dwindled pretty rapidly.

Drought and ongoing federal prosecution of polygamy (check out the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887 for some stimulating thought on church vs. state) put an end to Mormon ownership of the ranch. It became a National Monument partly because Pipe Springs offered a way-station between the Grand Canyon and Zion National Park, Today, the water rights are split between the Kaibab Paiute Tribe, the National Parks Service, and a group of descendants of the cattle farmers. The Kaibab Paiute (now numbering 200 souls) would still like to have the spring back, by the way. Ironically, of course, when the states came into being, Pipe Springs ended up in Arizona rather than Utah. Which is another thing we learned about Utah. Additional References https://www.kaibabpaiute-nsn.gov/KPTCEDS.pdf https://www.everyculture.com/multi/Le-Pa/Paiutes.html http://itcaonline.com/?page_id=1166 https://heritage.utah.gov/tag/the-paiute-tribe-of-utah https://www.deseretnews.com/article/865574356/A-visit-to-pioneer-oasis-Arizonas-Pipe-Spring.html On our 9000 mile tour of the western US, Captain Winnebago drove and moi –– his trusted Snactition –– ran the maps. Except for this one time... We had just spent a couple of halcyon days at what turned out to be one highlight of the highly-lit trip –– Custer State Park. We aren't fond of the historical figure, but his namesake chunk of land in the Black Hills of South Dakota? Really wonderful. More about that anon.

We had to go to Bare Butt State Park. How could we not? Like so many serendipitous moments while traveling, this came out of nowhere and delivered what we hadn't even thought to expect.

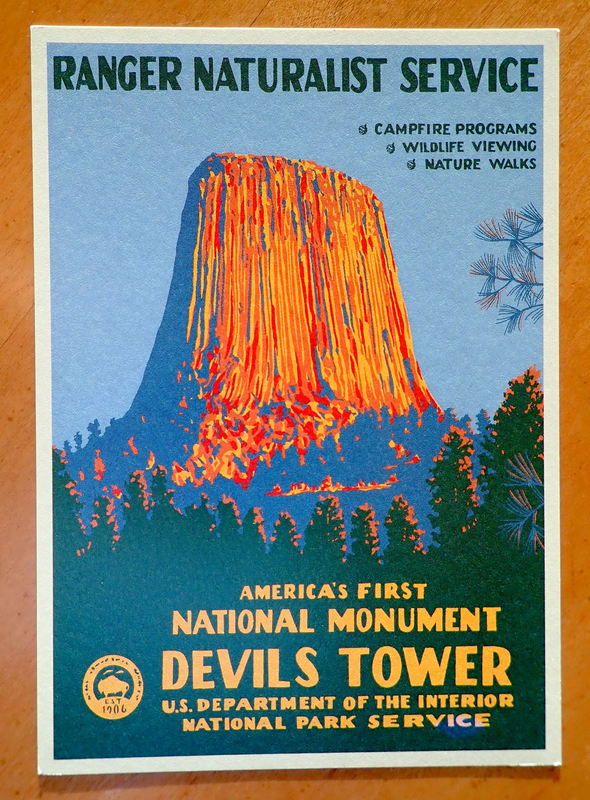

Like Devil's Tower, Bear Butte is an incongruously tall mountain in the midst of the high plains. It's mysterious and magnificent. However, Bear Butte is still in use as a spiritual center of Native American culture. Unlike nearly everywhere else we went, Bear Butte State Park was staffed by Native Americans, managed by Native Americans, and visited largely by Native Americans. I grant you, one day of hiking does not an expert make. But there's plenty of data for me to form some theories.

Nearly everyone we saw –– the shirtless dark-haired boys pelting down the trail at top speed, the elderly ladies in skirts assisting one another uphill, the dressed-up middle-aged couple wheezing asthmatically, the young family way way up the trail carrying their littlest up the ladder-stairs –– looks to us as if they don't need to be reminded of the mountain's significance. Before reaching the summit, there's a saddle where you can look for miles in every direction. You can see four states, though the big colorful Rand-McNally lines are not quite visible. If you were watching, you'd probably be able to see enemies approaching for a long time before they arrived. The wind blows right up the Butte from all directions. It's eerie. And beautiful. And it reminded us, for the next six thousand or so miles, that these astonishing natural wonders we treasure were also sacred ground for cultures that came before us. Even if people stopped leaving fabric gifts tied onto the branches like Tibeten flags, fluttering to the heavens.

From the prairies to the mountains to the desert and back to coastal Florida, a thread of rodential threat wove through our big park trip. Welcome to the Park...be careful of the rodents! Prairie dogs, which look like a slim, chirpy woodchucks and live in "towns" that stretch for acres, do in fact get the plague. As in Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that caused the Black Death, which wiped out an estimated 2/3 of the human population of Europe in the first half of the 1300's. Lucky for us, the disease burns through prairie dog towns very quickly. It's worth noting that the ranger did recommend that campers avoid handling dead prairie dogs, ESPECIALLY not if we happen to come across hundreds of dead ones at a time. No fear of that. I was not expecting the range of rodentia on the trip. The usual suspects –– red and grey squirrels –– showed up, while Uinta chipmunks, cliff chipmunks, red-tailed chipmunks, and grey-collared chipmunks also frisk about gathering nuts and startling hikers. Oh, the variations on chipmunks and squirrels –– like the Kaibab squirrel, which has enormous tufty ears and a white tail and can only be found on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. A fearful, shy creature (every family has its oddball, I guess), the Kaibab squirrel prefers the seeds of the Ponderosa pine over human leftovers. Bless them. Marmots are what happens when woodchucks take up mountain climbing. We spotted tons of Yellow-bellied Marmots. There's also a Hoary Marmot, (poor thing! His parents did not spare a thought for how that would sound) but he was even less photogenic. We spotted super cute kangaroo rats and thirteen-lined ground squirrels (once known as the leopard-spermophile, which just knocks me out). Out West, speaking of names, the common woodchuck or groundhog is known as a whistle pig. These creatures are universally unappreciated, whistle pigs. "They are good for sighting your rifle," was the comment we heard more than once. Also antelope ground-squirrels, which skitter away with the same flashing white butt as the prong-horns. Only much smaller, of course. Somewhere in the middle of the chippy-to-groundhog spectrum perches the ubiquitous rock squirrel. As a group, rock squirrels are fearless. They have the sleek look of the prairie dog, with chipmunk-ish tails, but with the shameless, aggressive begging native to a city grey squirrel. According to one park ranger, the rock squirrel is one of the more dangerous creatures at Zion National Park. They bite the hand that just won't resist feeding them. And that results maybe in stitches and a course of anti-rabies injections. Talk about unhappy campers. No fear of that on my part, but still. I almost wrote "It's hard to predict what they will do." But it isn't hard at all. They will search for food wherever they have the slightest chance of finding it (In a backpack? Yup! In the fruit orchard? Yup! On the sidewalk under your very feet? Yup!). And they will persist, twitching and chirping, whistling or holding unnaturally still from their various lairs. Squirrelishness. Fear them.

We formed any number of opinions –– about these regions, about this kind of travel, about the parks system, about the country –– that I can summarize, but probably won't. We had only one dud stop on our tour, and that was our own fault for getting the idea of place from television shows like "Bones" and "The X-Files."

Roswell, we both kind of imagined, would be dusty little desert town far from anything since about 1948.

We figured on stopping at the quirky little diner that we'd find there. Maybe we'd have a slice of pie amidst a collection of ephemera of the 1947 UFO wreck. The waitress would look a little like an alien. It would be odd and we'd have a story to tell. Instead, we drove stop-and-go through a medium-sized American city, complete with a Super Wal-Mart and a Panda Express, all the hotel chains and Applebee's. An unremarkable place with a touristy downtown reminiscent of A-Bay, NY or Ocean Park, NJ or Venice Beach, CA. Ridiculously disappointed, we slunk into an Albertson's supermarket (they had little-green-men balloons, etc.) for groceries and then drove to Dexter, New Mexico, where we found a peaceful berth for the night under cottonwoods and a wide starry sky. Just the one piece of pie with a side of story lacking for the whole trip. I'm not actually complaining.  The Chaumont Barrens. The Chaumont Barrens. In my 20's, having successfully survived my scholarship-funded undergraduate career and embarked on my first couple of real jobs, I was excited to start giving back to the world. I picked a couple of charitable operations that I thought would make an actual difference –– right away. The Nature Conservancy got the nod –– partly because of the romance of it: a bunch of business people taking a scientific approach to saving wild land and wild life –– and partly because I saw its work close to home. The Chaumont Barrens, an eerie bit of landscape from my childhood, is currently stewarded and championed by The Nature Conservancy. We used to picnic there, little knowing that the weird rocks and odd plants were remnants from the time of the last ice age. How the years do click by...My contributions aren't exactly princely, but I continue to fund the organizations I like. The Nature Conservancy rewards its donors with a newsletter, and I remember reading about the effort in 1989 to preserve a large tract of undeveloped tallgrass prairie in the middle of the country. It was a huge project, involving local ranchers and a whole consortium of foundations and philanthropists. The idea caught my imagination. I sent my modest donation and felt a sense of ownership when they bought the 29,000-acre Barnard Ranch, which has since become the 40,000-acre Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve. Restoration biologists searched high and low for some of the nearly-extinct plant species, finding some forgotten in the unmowed corners of old country cemeteries. Locating a few patches of those 6-foot-tall grasses that used to stretch across 142 million square acres of the Great Plains. The mind boggles. I imagined the scientists gathering handfuls of seed heads and nursing them to germination with that single-minded fervor known to any gardener. I kept sending my modest checks, noting with pleasure in 1993 when the first bison were reintroduced to the prairie. 300 of the large beasties were donated by a local rancher. Imagine that –– bison roaming nearly free! It was almost as if we didn't have to pave ALL of paradise and put up a parking lot. The herd has grown to around 2400 head of bison. Careful use of prescribed burns and herd management has meant that the prairie has continued to rebound, sheltering prairie chickens and bunches of the usual mammals in solid numbers. So when Captain Winnebago and I realized that we were able to make The Big Park Trip, I put Pawhuska, Oklahoma (home to The Pioneer Woman's Mercantile. Go figure.) on the list. It's not the vast stretches of unspoiled wilderness that our pioneer forbearers found, but after three and a half hours of driving through the property –– it's a reminder of how great the Great Plains were.

And if anyone doubts that truth, go on and continue driving north to the Badlands. |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed