|

Farming is hard. From the time Mr. Linton and I started this experiment (ooh, here's the first dispatch from the Would-Be Farm), we expected challenges. We welcomed challenges. Neural plasticity, baby! And sure enough, we learned some new stuff. We knew that rust never sleeps, but we found out that weeds will pull all-nighters all summer long in the interest of world domination. Looking at you, burdock. We discovered that even with zillions of established apple trees on the property, it's hard to get them to bear fruit larger than a golf ball. If the frost doesn't nip the bud, or caterpillars devour the leaves, or porcupine eat whole branches, well, then it's some other bug, some other mammal, some other weather phenomenon. And we have stuck by our decision to avoid toxic chemicals, regardless the wormy little apples. So when we have success, it seems the sweeter, and also, paradoxically, the fruits do not seem to be from our labors. Instead, it's as if they show up as serendipity. A gift from the farm. Passive agriculture. We put seedlings into the ground. Three or four years on, we see the first production of plums. Also, this year's single pear (yes: one fruit from the whole five trees), which has not been raided by raccoons yet. Does it count as work if we planted it so many years ago? Currents, aronia, and honey berries produced well this summer. For what it's worth. Tart, tart, and tarter. We have not, as my genteel mother-in-law puts it, developed a taste for them yet. Pro grower's tip: if the description in the nursery catalogue suggests that a fruit is used in jam or compote, beware. Tomatoes and garlic and potatoes are standouts again this year. Likewise those leggy volunteer cousins: fennel and dill, one bronze, the other pale green, popping up everywhere. I picked a bumper crop of blackberries (was it the extra rain? it's a continual mystery why some years do and others don't) but after the first disappointing pie––So seedy! So very seedy!––I set my sights on a cordial. I muddled pint after pint into mason jars of moonshine, which now lurk, dark and powerful, like untested ordnance, in the fridge. At this end of the summer, I tend to wander moodily around with a basket, swatting mosquitoes, marveling. It's a numbers game: we planted more than 25 modern apple trees, and only 5 are currently alive. And we have yet to see a single apple from those trees. We put in 20 hazelbert whips and though a dozen died for being planted in the wrong place, 30+ hazel shrubs flourish now. The eight elderberries I bought and nurtured over the past decade have yet to survive a third year, but the two newest? This year -- THIS YEAR! -- I will foil the deer. The six basket willow are growing by leaps and bounds, and have doubled in number. Of the five hackberry, I know for sure three are still living. The other two might possibly have slunk into the night. It's easy to find them in the spring, but once summer gushes forth––! The abundance of uncultivated food astonishes me. Things we never did a lick of work to encourage. Nanny berries and hickory nuts, big puffball mushrooms and black walnuts, not to mention, though I do, the free-range non-vegan options. So many good fishes! And ruffled grouse bursting from the underbrush would be happy, I can see in their ruthless dinosaur eyes, to dine on me in the rather likely event that they SUCCEED in startling me to death. And then there are chickadees, who chatter when the birdseed is running low. One or two of these lillies of the field are especially bold. They barely need coaxing to land on my hand, where they look me in the eye and take their time picking a seed.

I've really done nothing to earn chickadees. But I'm grateful that the Farm has provided them too.

12 Comments

And –– But –– My favorite skipper eventually called it: mad dash. It will seem quaint someday how we drove north in a self-contained little world of snacks and Lysol wipes with a U-Haul full of Would-Be Farm equipment and furniture. It will be just another page in the Quarantine Chronicles how we isolated and monitored. Perhaps we'll remember how we could only hope our precautions and cheerful masks will have made a difference. But it seems instead that this is the year we are reminded that Mamma Nature not only holds all the cards, but that she has sharp teeth, and claws at the end of a long reach... If it wasn't the black bear emptying the bird feeder (effortlessly snagging it with a claw and pouring the contents –– like the crumbs from the bottom of a potato chip bag –– right down the old pie hole), it was porcupine eating the gazebo. Or birds flying down the chimney. And how does one deal with a 300-lb black bear with a penchant for black oil safflower seed? One puts a decorative cow-bell –– an inexplicable tourist purchase finally coming into use –– onto the formerly lovely red metal feeder. Pavlov's crazy dog at the midnight clank, one dashes onto the screened porch closest to the feeder, shouting and clashing together an aluminum saucepan and lid. The noise was like nothing I have ever made before. It worked. Though of course the raccoons followed the bear in the violation of my bird feeder. They are less shy of human attention. After some weeks of interrupted sleep, I decided the easier –– though not unproblematic solution was to take the feeder inside at night. Now I only rouse myself to chase things off the unscreened porch. Which happens a lot. And how to address the ongoing porcupine issue? Porcupines eat bark and tree parts...unless of course they develop a taste for pressure-treated lumber. Fair's fair. The porcupines were here first. I tried putting rows of hardware cloth around the perimeter, but Mr. Linton took the reins. We call the gazebo The USS Monitor now. The damage has stopped. Sidebar fact: tom turkeys sometimes get really worked up by the sound of a carborundum blade working through metal roofing sheets. I guess it sounds like a big sweet gal of a hen. And as for the bird, we were sitting on the couch in front of the cold wood stove when we heard a gentle tapping on the glass window on the stove door.

A youthful house-wren politely requesting a hand. Of course it panicked. All birds do, when confronted with the inside of a house. It flapped into a window, and then briefly fainted in Jeff's hands. But it eventually regained its senses and flew off, rewarding us for a few weeks –– possibly –– with extra noisy morning songs. Everyone knows someone who is irrationally (well, that's all in the perspective, right?) afraid of, say, legless reptiles or eight-legged wall-walkers. Not just slightly averse to these creatures, but seriously, panicky, clawing-a-way-out-the-window fearful. Each of my parents had one. For my father and his siblings, having survived a canoeing accident as children where they and their mother clung to an overturned boat while long strands of seaweed brushed their legs, the fear was snakes.

I never noticed Mumsie's issue until that first summer at the cottage. We'd gone to take a quick look at what they had purchased –– waterfront! as is! Bill Bailey blue! furnished with toys and musty furniture! –– on the shore of Lake Ontario. We ended up just staying all summer. Daddo went off to work downstate during the week while the three of us swam and read books and played with the neighbors (each according to her tastes. Mumsie was not much for running around pretending to be horses). Naturally, given the body of fresh water, the long Northern summer days, and the untenanted nature of the cottage, there were spiders. But it was a summer cottage. When sweeping, you directed the little pile of debris down that knot-hole in the floor in the hallway. On Thursdays, before Daddo came up, we'd eat ice-cream for supper. It was a Platonic ideal of summer cottage life. Except for the spiders. One morning, we all scooted out of the house while Mumsie sprayed some sort of aerosolized poison. We must have been gone all day. Or maybe it was stormy when we returned, because while my sister and I, diminutive then, walked into the shadowy cottage without incident, our mother entered to a suspended carpet of deceased arachnids. All hanging at about eye-height from the ceiling. The horror. The horror.

Eventually, she dredged up a memory for me. "It might be this," she said, draping her paperback over her knee. "When I was very little –– on the farm in Springville –– I was playing in the creek." [The word "creek" in the geography of rural northern Pennsylvania was pronounced "crick." A thing I miss from her.] She turned her head in the same questing way as when she was trying to recall the details of a dream. "I was splashing the water with a stick and there was an enormous water-spider. I hit it and it burst open and dozens –– hundreds?–– of baby spiders spilled out." Gulp. Okay then. My sister shares the distaste for spiders. We've often agreed that should there be an unfortunate single-car accident in her life, it's a near certainty to have involved a spider emerging from under the dashboard and landing on exposed skin.

As for spiders? I understand they won't actually kill me, but I find it hard to casually look away once I've noticed one nearby. I find their globular bodies shudderingly distasteful. Be that all as it may. I actually meant to write about weird phobias. There's no shortage of oddity in the world. And phobias are the most common of mental illnesses. Mental illness. Huh. I've felt claustrophobia. Couldn't get into an elevator for two years. It was a side-effect, I think, of a dreadful boyfriend and asthma. Once I nearly fainted –– and me a farm kid! –– at the vision of a big splinter protruding from someone else's finger. All the blood and guts in the world, and I was about to keel over from a splinter. I couldn't even help her yank it out. But that's pretty mundane stuff. What's more intriguing is the fringier fears.

One of our elders has what's known as "White Coat Anxiety." Whenever confronted with a doctor or medical professional in a clinical environment, her blood pressure goes sky-high. I worked with a woman who couldn't stand scissors. We'll call her Peg. Another co-worker, Liz, a capricious but observant creature, had noticed that Peg invariably moved books and files so that a pair of shears on a colleague's desk would be hidden from her view

The story varies. In any case, Galápagos mockingbirds are also distinctively different from mockingbirds on the mainland. And they are different from one Galápagos island to another. Which leads, step by painful step, to Darwin's theory of evolution and the eventual publication in 1859 of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Phew. Sidebar drama: Interestingly enough, as a Christian, Darwin was troubled by the implications of what he discovered. However, when a naturalist pal of his, Alfred Wallace, came up with a parallel theory, Darwin's misgivings subsided enough for Darwin to polish up his own manuscript and send it to a publisher. It became an overnight sensation. While we were doing our own exploration in the Galápagos (zero collection of specimens, thousands of photos, great guides, and a tidy ship thanks to AdventureLife), we stumbled across a little mockingbird family drama on Floreana. I've got a theory or two (as usual) about this scene. It might be a long-held rivalry between the matriarchs who were born sisters but grew to their own greatest rivals. It might be a fresh incursion between an upstart gang and the Boomer family they rejected.

Or maybe it's a daily show staged to entrance the tourists –– 14:00-15:20 beached walrus pups, 15:20-15:40 mockingbird display, 15:40-whenever tortoise crossing. So, okay, maybe the big raptors like Bald Eagles and Snowy Owls are more impressive, and coming eyeball-to-eyeball with a Sandhill Crane is even more alarming, but Great Blue Herons are darned impressive birds. In my Shell Island Shuttle days, when we'd rescue birds –– mostly untangling them from fishing line, but sometimes popping them into a pet carrier and ferrying them over to the local rescue outfit –– the Great Blues were among the most challenging to help. They are fierce, even as they are fragile. Those long legs ––! They aim those impressively big beaks RIGHT for your eye, and they have quite a reach. They do not give up after they've been caught. Magnificent, cranky creatures. In a book whose heavy style I enjoyed a lot –– though, sadly, after my godfather Dan complained about the many factual errors he'd found, and I did my research, I too, became less enchanted by the novel –– here's a lovely passage including a blue heron: In his mind, Inman likened the swirling paths of vulture flight to the coffee grounds seeking pattern in his cup. Anyone could be oracle for the random ways thing fall against each other. It was simple enough to tell fortunes if a man dedicated himself to the idea that the future will inevitably be worse than the past and that time is a path leading nowhere but a place of deep and persistent threat. The way Inman saw it, if a thing like Fredericksburg was to be used as a marker of current position, then many years hence, at the rate we’re going, we’ll be eating one another raw. And, too, Inman guessed Swimmer’s spells were right in saying a man’s spirit could be torn apart and cease and yet his body keep on living. They could take death blows independently. He was himself a case in point, and perhaps not a rare one, for his spirit, it seemed, had been about burned out of him but he was yet walking. Feeling empty, however, as the core of big black-gum tree. Feeling strange as well, for his recent experience had led him to fear that the mere existence of the Henry repeating rifle or the éprouvette mortar made all talk of spirit immediately antique. His spirit, he feared, had been blasted away so that he had become lonesome and estranged from all around him as a sad old heron standing pointless watch in the mudflats of a pond lacking frogs. It seemed a poor swap to find that that the only way to keep from fearing death was to act numb and set apart as if dead already, with nothing much left of yourself but a hut of bones. Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier, 1997. Page 16. PS: I actually prefer Cold Mountain the movie. Exception proves the rule.

Half asleep in our narrow berth inside Base Camp, we are roused by sound: a crunching, rattling, scratching assault on the recycling container, a lengthy effort to unsnap the cooler, a hissing dust-up over a piece of aluminum foil that once held roasted chicken.

Eventually, Mr. Linton or I will have had Just About Enough and shout at the intruders. Angry-Daddo-Voice invective, which sometimes works, but does require warning the other person. ("Hey, I'm going to yell." "All right." "GERRROUT OF IT!") Scamper scamper scamper.

This autumn, they discovered both suet and the bird feeders.

As Jeff put it: they ate a whole LOAF of suet. Naturally, they knocked a bird feeder over and emptied it also.

However, the raccoons did.

The first morning, I found the jar tipped over, the lid unscrewed and a small, tidy spill of seeds on the porch.

In the morning, the birdseed was not on my mind. I was blithely drinking my coffee and being all China-to-Peru about the dew-laden field opposite the porch.

I changed lids and put the jar inside. Thin the tin walls of Base Camp may be, and permeable as sponge, but there is a geographical limit to transgression.

You'd think, anyhow. When the light slants just right, a distinct handprint can be seen on the window that looks into the sleeping nook at Base Camp. Maybe two inches across, the little handprint is smeared on the window that stands a good three feet off the ground. I try not to imagine why a raccoon climbed up and appears to have pushed –– pushed!–– on the window that looks into our sleeping quarters.

Nevertheless, I find myself weighing a few options:

Which is where I hit pause. The bandits were here first. They raid for a living.

I'll start by making it prohibitively difficult for them to get satisfaction around Base Camp before taking lethal steps. Muah ha ha. Pariediolia is the name for the native human tendency to construct faces out of random patterns. Like Arcimaboldo's work, but by chance rather than art. The word comes from the Greek for something like "wrong image." Spotting the face of St. Lucia on your flatbread pizza –– mental illness notwithstanding –– is bonus in our evolutionary heritage of pattern recognition. It's related to the way that when confronted with a paper plate decorated with bull's eyes, a wee bitty baby serves up the same charming goo-goo eyes for the plate as he gives to actual human faces. Survival of the most charming. Which tells me that the point of imagination is to actually and genuinely save your life. But what's it called when you spot horses everywhere? Each spring, one of the first pleasant chores at the Would-Be Farm is a nice mix of high tech and low mud: we retrieve the game cameras and make our observations of the winter action. Some old friends appear year after year. And a few surprises. Even with thousands of images captured on the tiny photo cards, some creatures are still camera shy. Others pose. While a couple are hiding in plain sight:

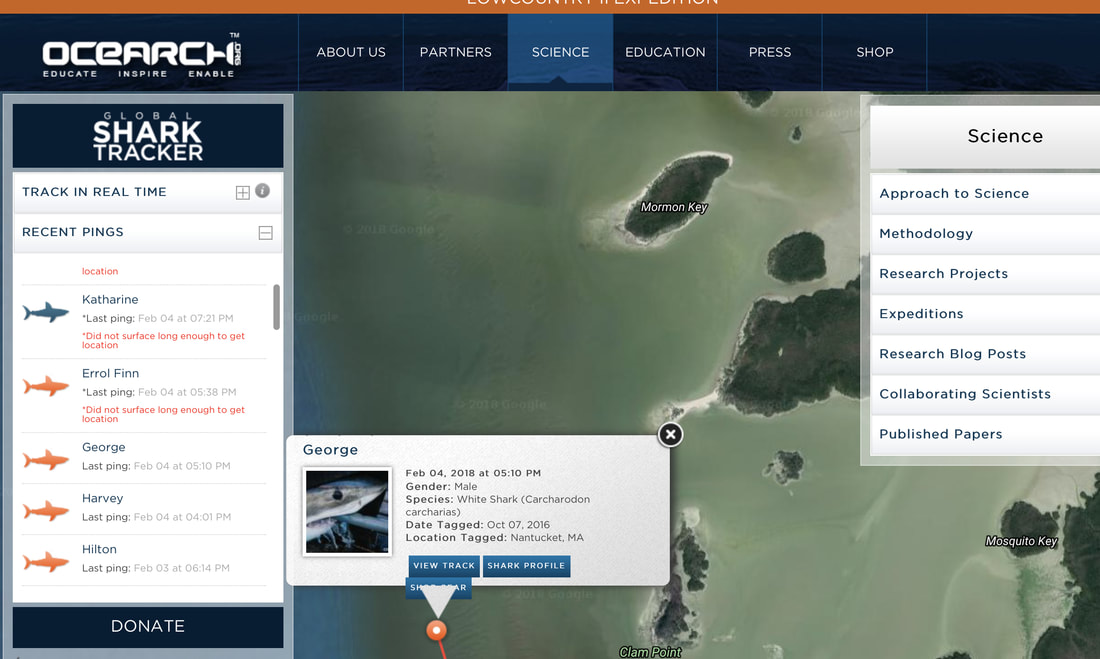

We'll camp in the Everglades National Park. It's not our first venture into this wilderness. It's a place less full of shady Spanish moss and swampy mud than one might expect. It's pretty darned pleasant, actually: we pitch a tent on the sandy beach, maybe catch a few fishes, play with driftwood. In general, the hazards that are most worrying on this venture off the map are, oh, I dunno –– mosquitoes, sunburn, getting stranded and having to be rescued. THIS is not what I expected: Mormon Key is our favored camping spot. George was almost 10 feet long last time they checked, and weighed in at 700 pounds. Good lawsey day.

More Everglades Challenge? Okay, here's a story about the adventure race by the late great Meade Goudgeon. We'll miss seeing him on the beach this year. The Challenge starts on March 3 off Fort DeSoto Beach. One of the many pleasures of returning to the Would-Be Farm is the ritual of checking the game cameras. As we have gotten to know the various gamey crossroads, we've added to the numbers of these nifty little devices. In fact, this time we forgot where we'd put that one for several days... *Sidebar factoid: the term "paparazzi" comes from the name of a character in the 1960 Fellini film La Dolce Vita. That name (Paparazzo) also harks back to a kind of large Italian mosquito. A few highlights from October 2017 at the Farm.

|

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed