One of my writing friends, Cath Mason, is a poet. Lest this conjure an image of a clichéd fright speaking in sing-song doggerel about spring flowers, let me assure you: Cath is a good poet. Funny, sharp, clear-sighted. She writes about peculiar and very specific things, such as a baking potato that jumps out of its own skin in the oven, or the octopus in a German zoo that makes a habit of rearranging the furnishings of its tank. Her website is here. She's the kind of person for whom friends clip odd articles from the paper. She dips into esoteric books on quantum physics, fractal geometry, the mating habits of songbirds. Recently, she revealed that she'd learned the answer to this question: "What strange South Asian mammal smells like a batch of fresh-buttered popcorn*?" and that she could imagine creeping through the jungle, sniffing, and saying, "Is someone making popcorn?" (*Answer: the Asian bear-cat.)  Cath and I meet for writing sessions when our schedules permit. Sharing a table at a coffee shop and hunching separately over our notebooks, we come up for air and company every few hundred words. One morning, she told me that one of her great and abiding joys was tea and toast. She's from Lancashire, in the northwest of England, which anchors her opinion with a certain gravitas. It was not just the crunch, she said, and the strong flavour of tea (it's hard not to adopt the British spelling to align words with accent), but the moment itself: the house quiet and herself alone with her mug of tea and a piece of toast. I rarely have toast. French toast, yes, of course: as means to a maple end. And of course, toast is the only way to corral a BLT. But toasted slices of bread? Solo? Buttered? That's just crazy indulgent.  And yet. Today I found myself watching the toaster-oven do its slow thing: glowing and incinerating invisible crumbs, bending the air with heat. I took a sip of tea and wondered about this imprecise process. Not knowing how the toaster oven -- set midway between "Light" and "Dark" -- would perform, I couldn't let my attention drift. As it is wont to do. It's a vocational hazard for writers, daydreaminess. I would never describe her as ditzy or absent-minded -- still, Cath does seem to save her deepest attention for the things that most catch her interest. Like strange potatoes and jungle creatures that smell of popcorn. Keeping an eye on the untried toaster-oven, I wonder: is close observation part of what brings Cath joy? To be present during the transmogrification of plain bread into something golden and fragrant? While I pondered toast and attention and writers, the toaster oven tried to do its darnedest. The aluminum body barely containing a dragon's instincts to singe and carbonize. I prevailed. The result was lightly toasted, a slice crispy yet tender, with a perfectly melted skimming of something butteresque. It was sigh-worthy. Absurdly gratifying. Perhaps tea and toast is but a minor joy in the wider constellation of wonders stretching around us, still, it deserves its moment of appreciation.

15 Comments

"Camry? Me likey Camry. Nom Nom Nom." "Camry? Me likey Camry. Nom Nom Nom." Like some other birds, vultures spend their winter months soaking up the sun and playing canasta with their friends in the sunny South. Or anyhow the carrion-eater's version of canasta, which seems to involve the rubber gaskets of your car windows and doors. The park angers warn you upon entry to the Myakka River State Park: the vultures will nibble any exposed rubber on your car. They'll peck away the seals on your windshields. They'll chomp on your sidewalls. And they are good at this: they can remove the weather-stripping from a mini-van in under an hour. ...No, the rangers don't know why these creatures do such a thing, but there it is. A vice. Among vultures.  Our annual Christmas camping trip a few years ago brought us -- Jeff and me and the small dog -- to Myakka River State Park. (It's a thing we do, hopping into the RV and nipping away for a day or two over the holidays.) Myakka is a couple of hours south, a pleasant enough drive. It boasts 57 square miles of wilderness with an oak-canopy walk, wide river-of-grass vistas, and a whole lot of alligators. It's rightly billed as "Where the River and Prairie Meet the Sky." But the camping area itself is surprisingly compact, with tents and camping vehicles and portable dog kennels and such packed tightly. A crowded little island of humanity. The racket of generators and recorded Christmas songs and people shouting quickly nudged us on a long walk with the dog after sunset.  Less than a hundred yards away from the camping area, along the paved road still radiating the day's heat, artificial sound faded. We swept flashlight-beams into the trees, hoping to spot bats or flying squirrels. With the lights switched off, the dark seemed to first press in close and then back away. The stars were bright in the gaps between the oak boughs above. When we stopped to listen, we heard coyotes in the distance, the sound incongruously dry for the marshy surroundings. We walked on, silent, the little dog leaning, in her Boston-Terrier way, at the end of her nylon leash. The yipping and howling got a bit louder -- whether clearing some sound-break or growing closer it was impossible to say in the dark. Then the sound of the coyotes was much closer still, and Jeff said, "This is not good." "Don't worry," I assured him. "They are shy. Listen to them." Jeff knows about alligators, sure, I was thinking, but I know canids.  And our dog was snuffling unconcernedly at the pavement. She's a good watch-dog, our Lilly. She pipes up when there's conflict. The yodeling, yelling, yapping cries -- continual now -- grew very loud. There were at least several different voices, all talking at once, the sound like the torment of souls. As anyone who's been camping in Florida can tell you: an armadillo the size of a meatloaf moves through dry palmetto with roughly the same sonic footprint as a marauding elephant. By the volume of their vocalizing, the pack could have been right next door. It seemed remarkable that we didn't hear the pack moving through the underbrush. Then nothing. As if someone had shut off the radio, the silence stunned and absolute. Jeff's alarm infected me. "Come on, dog," I said. I jiggled the leash and she, still unconcerned, obligingly turned back the way we'd come. Night fog was settling as we crested a small rise, and then -- as we entered the damper, misty bit of lowland -- we could smell the pack. The scent clinging to the fog was rank, musky, unmistakably wild. "They are probably watching." Jeff said, his voice low. We skedaddled back to the lights and the noise of the crowded campground. We listened intently for the coyotes to resume their serenade, but they kept silent. Probably watching.  Thanksgiving feast sporting a fine bacon waistcoat. Thanksgiving feast sporting a fine bacon waistcoat. The next day at the ranger station on our way out, I told the ranger. "We heard coyotes!" I recounted how while we were walking our small dog, we'd heard a chorus of them. How they'd come close, closer, then went silent. How we'd picked up their actual scent in the hollow. "Next time," the ranger said, his voice calm as he stamped some papers. "You might want to pick up and carry the little dog." I repeated the ranger's words as Jeff steered the RV back through the gates of the park. "Next time," Jeff echoed the phrase, consideringly. "Next time, we'll make her a little bacon-suit." "Gah!" I replied. Then, "Hey!" Outrage rendering me inarticulate. Keeping eyes on the road, he said, "Who doesn't like bacon?"  This gopher tortoise does not give a hoot about caption contests, but then again s/he probably does not have a stock of quasi-fabulous prizes to award. Leave a caption as a comment below -- the contest will be open for some random period of time until a clear frontrunner emerges. And oh yes, there will be prizes.  As our planned 2014 Everglades Challenge entry, Frankenscot, has been taking shape from a classic Flying Scot sailboat to something a bit more weird-science-y, the project threatens to ooze into every corner of our living space. At first, the necessary gear for TwoBeers and Moresailesed formed a small mountain in the living room. We moved it between venues and the mountain grew as we added sleeping pads, a solar recharging pack, charts, collapsing water jugs, GPSes, whistles, dry-bags, bug juice, duct tape. Before long, the stuff formed two mountains, three, and continued to rise. Flashlights, handwarmers, camping cookware, EPIRBs, more dry-bags, mylar blankets, running lights, survival knives. It was like an Icelandic volcano spewing water-proofed technical fabric and nifty camping equipment. In our very own living room! An unnatural miracle! Weird science!  But my tolerance for chaos has an outside limit. As Daddo used to say, "You can do things right, honey, or you can do them twice." Or you can do it a half-dozen times, when it comes to organizing a disorderly mountain range of survival gear. Bring on the IKEA carry sacks. Who knew that FEMA-blue tarp could seem actively cheerful? Who knew that smurf (not amber) is the color of our energy (whoo-ooo)? Plus -- be still my tight-fisted heart -- they cost 55 cents a piece! Such a value. Suddenly, the mountain range is tamed. A big blue IKEA bag of sleeping gear! A big blue IKEA bag of electronics and cooking stuff! A big blue IKEA bag for clothing! When it comes time to transfer Mondo Cargo Mountain yet again, those big blue IKEA bags have handles, and they resist water. So when settled for a moment on dewy grass while someone runs back upstairs (Gah!) for the key and then wrestles open the cargo doors on the van -- no problem. Water stays on the outside, stuff stays put. At least on my shore-side watch. How do you move the world? A big lever? Sure -- or take it one bag at a time.  Like many a fool before us, we bought land on a whim. It might have been a whimsey of long standing, but the purchase cannot really be described as sensible. A hundred and some acres of former dairy farm, a ramble with only the rusted ghosts of barbed-wire fences and a tumbledown house to show for it. The property boasts hardwood and piney woods, vast stretches of thorny underbrush, meadows blithely reverting to marsh, deer-hunting stands of uncertain provenance, and a choice assortment of random boulders and sheer granite rock-faces. But a lovely path meanders from the road at the front of the property to the pond at the far end. The path curves through the strips of meadow and upland woods like an invitation. And the pond, ringed with sharp stumps (like huge mute pencils stuck into the soil eraser-end first), has more than one active beaver lodge.  We picked the land for beauty and for the potential of future use. It's no less sensible an investment, look at it from another view, than purchasing art or a fancy-schmancy car. No car, even this one, comes standard with porcupines and kingfishers. It begs the question of why: Why buy land so far from where we live and where we plan to continue living? Why not someplace within easy drive of home? If we meant to spend time with the northern relatives, why not get a summer cottage instead of what the tax office so flatly describes as "wasteland"? In a word: apples.  It's perhaps the single thing I miss by living south of the 38th parallel, and one of those crops that might -- just might -- thrive without a year-round caretaker. We spotted a handful of old trees on the land on our first reconnaissance sorties, so there was potential. Plus, you know, new neural pathways. If a person want to remain relatively sprightly, so the research is showing, she should start early by making new neural pathways in her brain. Move house, start dance lessons, take up fresh hobbies, forge new connections to the world, and put your muscles to work in unexpected ways. Thus was I thinking: maybe start with a dozen apple trees. Get saplings in the spring. Carefully shielded from the deer and the voles, planted in the best-looking stretch of meadow, now THAT's a nice new neural path. The chicken-and-egg quandary about when to sink a well and when to pipe in electricity to pump water out of the well to give the baby trees a drink? Delicious question, because after all, our very own orchard! The neighborly dudes down the road agreed to mow our overgrown pastureland in exchange for the right to hunt over the winter. A sailing friend in the Finger Lakes raises apples; when asked, he agreed to share some insight. And I started taking farming classes through the Cornell University Cooperative Extension.  Ask any wee sleekit cowr'in beastie, and he'll tell you: Plans. Bah! Aft gang agley, plans. Those handful of gnarled old apple-trees that we'd seen while scouting the land? Just the start. Scrambling up and down the ridges, checking the property lines, Jeff and I found two groves of 30+ mature trees -- untouched, I think, by human hand for decades -- and dozens of full-grown volunteers all over the place. In total, perhaps 100 trees. Which has led to the purchase of our first piece of farm equipment: a chainsaw.  Halyard box (w/upgraded stainless crank) Halyard box (w/upgraded stainless crank) As anyone who has sailed a Flying Scot knows, the class design includes a unique halyard arrangement. (A "halyard" is the nautical term for a rope or wire that raises a sail.) The halyards dead-end in a halyard box on the mast. Inside the halyard box are a pair of metal spools. Each halyard (one for the jib, one for the mainsail) is wound around these spools by means of a dinky Model-T-style hand-crank. It's actively ridiculous, this system, reminiscent of a hamster-wheel -- one designed as a miniaturized Steampunk contraption that's needlessly and unscientifically complicated. Complaints about the hamster-wheel are legion: the hoist is imprecise -- too tight or too loose by half a click. The spools jam. The stoppers fail. The halyards kink and override on the spool. Hand-cranks tend to leap wildly overboard during moments of excitement. The standard cranks -- made of pot-metal -- sheer off inside the mechanism on a regular (if unpredictable) basis, leading to all kinds of unfortunate finger-pointing on the boat, and name-calling, sometimes even descending to scratching and tattle-tale-ing. Tsk. Tsk.  Still, year after year, the class has kept the halyard box, despite (or perhaps because of) its shortcomings. Since the Frankenscot stopped being a Flying Scot after the first application of the Sawzall, the boat is not subject to those class rules. This was one of the first modifications we planned: to put on a Lightning-class style claw-and-ball system -- so that a few arm-over-arm yanks raise the sail and then the halyard slips into a sort of hook to hold it in place. Simple, quick, easy. It's ironic that this whacky-doodle little halyard box is one of the very few parts that persists unchanged from the original conformation of the Frankenscot. But then, as our source-text and inspiration, we have.: “In other studies you go as far as others have gone before you, and there is nothing more to know; but in a scientific pursuit there is continual food for discovery and wonder.” Perhaps the hamster-wheel contains the very spark of Flying Scot-ishness. As it were, FrankenScot's soul. In the interest of keeping the townsfolk from riot, or in the pursuit of expedience (less than fifty days to go!), perhaps it should keep its place.

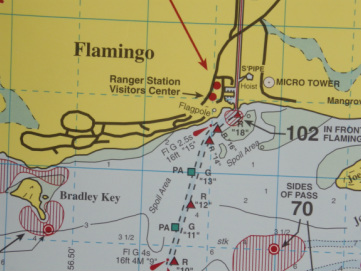

Or not. We'll see.  Sometimes at night, the small dog will trot to the bedside. Stomping her toenails on the wood floor and breathing extra-loud, she'll roust us for a trip outside. She's subtle but insistent. If we don't react, she snorts. Ignored long enough, she might escalate to a stagey sneeze or two, the castanets of her feet going double-time. Bless her heart, I remind myself as I swing my feet onto the chilly floor, better she wake us than leave an accidental present on the carpet. When she descends the stairs under her own steam, Lilly's outsized Boston-Terrier head makes the process tragic and funny. It goes like this: one step, two steps, hop hop, things speed up -- the teeter-totter tips -- and she tumbles down the last few steps. She regains her feet after this noisy disaster with only a brief, wincing look of confusion, but I can't shake the idea that she'll break something falling that way.  So now, I sit on the top stair while she clambers into my lap and I convey this grunting sausage-roll of dog in my arms to the lawn. She's also perfectly amenable to being carried in a canvas ice-bag, like a fat-eyed load of firewood. When encouraged, she'll step over the folded side of the bag, ignoring the indignity of having her narrow butt tucked into place, and wait, frozen, blinking, enfolded in stout fabric, until back on solid ground. She loses track, from time to time, of what she meant to do on the lawn. Standing motionless under a big moon, she seems to be sleeping with her buggy eyes wide open. Urged to "be a good dog," she snaps out of it, giving me an apologetic look before attending to the chore. Told that she is being "a good dog," she flattens her ears at me, even while she balances on three legs. As soon as she can, she speeds away from the scene and back to my feet.  Sometimes she'll pause at the bottom of the steps and give me a look. Perhaps she's hoping for a boost. "Hup, simba," I tell her (the words a reference, I should be ashamed to admit, from Tarzan cartoons, not David Foster Wallace). And up she hops, occasionally missing her footing but steadily ratcheting her way up the stairs and then bee-lining it back to her dog-bed. In daylight, a treat is the normal reward for "being a good dog," but I learned my lesson the first week she slept under our roof: do not reward her midnight runs with dog-biscuits or else she will be at it non-stop -- sneezing and clacking her repeated demands for midnight runs and dog-biscuits. Even a good dog can be trained into a tiny tyrant.  Shocking, isn't it? Not only did they spent their days messing with the tides of war and chasing an unsavory amount of mortal tail, but the Classical gods evidently shared our smart-phone addiction. I'm hoping that this guy here is not Apollo glued to his LOLs and OM-me's. For one thing, the full and manly beard is not Apollo's style. Plus he didn't need the distraction while piloting his quadriga across the sky each day. Texting and driving is not funny. Maybe it's Zeus -- or rather, since I snapped this picture on the Capitoline hill in Rome, maybe it's Jupiter. I wonder if Jupiter checking out that selfie Janus posted. [she said, snorting nerdishly] Maybe he's checking his Twitter account (#makelikeaneagle@HotSedele, #makelikeaswan@HotLeda, #makelikeasexybull@HotEuropa), or watching that Instagram parody. So what -- and who -- is he texting? Entertaining caption below wins a prize. (Note, at press-time, the previous caption contest ("Caption Contest #1: The Dogs") is still open to entries.  The Everglades Challenge sends a fleet of adventurous boating folks on a 300+ mile voyage from Tampa Bay to Key Largo in March. We've been hard at work on a highly modified Flying Scot we're calling Frankenscot that we hope to enter into the event.. A trip like this is not like gassing up the station wagon and hitting the highway. The course includes three check-in points along the way. Between here and there, we have open water and the Gulf of Mexico, various rivers and marked channels, mangrove islands, the Intracoastal Waterway. Plus, in this race, there are no rules against -- say -- cutting a corner and yanking the boat over shallow spots on foot, if need be.  Moresailesed and TwoBeers, December 2013. Moresailesed and TwoBeers, December 2013. Plotting a 300-mile course along the left side of Florida and through the 10,000 islands of the Everglades means making provisions for alternate routes, and alternate-to-the-alternate routes, and third-option-alternate routes. Is it better, one might consider, to stay inside the barrier islands or in the Gulf if the wind is piping up? It's not just the volume of breeze, but the direction, the likelihood of the wind backing or clocking (changing direction, in sailor-parlance), and of course the sea-state. Plus the tide, the waves, the time of day (it's good to avoid high-traffic Saturdays, for instance, along some of the stretches of water), etc. etc. etc. As with so many human endeavors, it's best to think about the options early: if it's dark and stormy and something (knock wood) goes bang, it's good to know already where to bolt to make repairs or take shelter. Far better to have already figured out that Tin Can channel is not recommended in certain wind conditions than to try to figure it out in the middle of the night. With the wind in the unfavored quarter. To that end, taking advantage of Moresailesed being in town, TwoBeers and Moresailesed got together recently to test the boat and to meet with Jarhead.

The veteran of seven Challenges, first single-handed finisher in Class 4 in last year's EC (aboard a SeaPearl), and proud former Marine, Jarhead has been openhanded in sharing his wisdom. He may see us as young whippersnappers, but he's willing to tell us what he thinks about routes and alternate routes, especially for the toughest spots of the Everglades Challenge. With an amber FatTire close to hand, Jarhead walked an attentive group of sailors through his main navigation points. As he talked, the crowd built. Nothing speaks to sailors like experience, especially about something as tricky as nighttime, sleep-deprived navigation. My pages of notes include things like this: "Hug the shore to the lights on Chokoloskee Bay. Head for the lights, not the dark." And: "It's very tough to tack in the channel on an Easterly. Here's a thing to remember: if you are going to go aground, get stuck on the upwind side of the channel." And, yes, we resolved to squeeze in a few more reconnaissance trips to Florida Bay before that March 1st starting line. |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed