|

There are too few hours in the day, even as the days grow longer in leaps and bounds. When we arrived at the Would-Be Farm in early April--in time to spare for my sister's birthday and the total eclipse-- the sun was up from 6:30am to 7:34pm. On the day we left, the sun peeped up at 5:40 and lingered until 8:19. At midsummer, according to the 'webs, it'll be 5:30-8:45. At that latitude, twilight and pre-dawn last for ages. Every year is different, of course ("It's a planet, Jim, not a calendar."). This year Spring sprang extra early. The daffodils that I would hope to see the first week of May were blooming their faces off the second week of April. Early spring meant that only a few plants that I treasured were nibbled into oblivion over the winter. It also, critically, meant an early fishing "bite," as they say. I was grateful that Jeff and his fishing captain, Dan ("Captain Dan! Captain Dan!") stuck to the inland lakes and the little bitty tin boat, because early thaw or no, that water is co-co-cold. Each year, I worry about pollinators showing up for the many feral apple trees, and for the handful of sturdy fruit that have survived our custodianship (looking at you, pear trees!). ...and was reassured again by the pastoral hmmmmmmm of a battalion of bees working the trees. It's one of the unexpected sensory pleasures, to stand among fruit trees in early spring, listening to the sound of insects at work, ensuring the annual miracle of fruit growing on trees. The bees are noisy, but there are other, quieter pollinators to observe: butterflies and moths, damselflies and wasps. Hummingbirds, orioles. We run an all-you-can-sip buffet out there. In the past decade, I've grown accustomed to the sloth pace of the season: first bluebells and rock iris, a few days later, maybe a touch of snow, and then Dutchman's britches and early saxifrage, a few more days for the first hint of wake-robins and daffodils. Buds will start to swell, and the hint of green will return to the putty-colored fields. Bluebirds and bright goldfinches will look like confetti scattered in the wind. These and less crayon-ish birds will be making a racket earlier and earlier in the morning. Then maybe spring peepers will start up, along with the excited hooting of barred owls and the good-lord-that's-annoying-after-the-first-three-times sound of the whip-o-will. This spring, everything seemed telescoped into a couple of weeks. By the time we migrated south for our annual pilgrimage to the Florida Keys (fishing! friends! regatta!), new leaves the color of radiator fluid stippled the woods. Like an inverted dance of the seven veils: the naked rock bones and tree trunks covered by swirling layers of buds, blossom, tiny leaves, bigger leaves, a variegated canopy, dressing rather than undressing. Though, naturally, we hope not to begin (or end) with someone's head on a platter.

0 Comments

The Would-Be Farm has had a wet 2021 summer. The grass grows like weeds. The weeds grow even faster. But the flowers have been pretty glorious, honestly. Last year, my long-suffering sister agreed to start some of my eccentric seed choices. In March, when gardeners in the North Country begin to stare longingly at anything green in hopes that it might be alive, grow-table real estate is valuable. It was a generous offer. So I sent packets of ground cherry seeds, monarda seeds, borage seeds with my hope. The ground cherries refused en mass to start, and the borage, once started, too closely resembled a weed and in June was twice accidentally whacked and gave in to entropy without fuss. But monarda –– monarda was the standout: each seed sprouted and refused to be cowed by last summer's drought. Back in April in that first plague year, under the grow-lights, my sister sister looked at the monarda starts with suspicion. "Are these," she asked me dubiously, "bee-balm?" Me, consulting the inter webs: Um, yes. No wonder these seeds had sprouted: the stuff had taken over a whole corner of her flower-garden. I could have as much as I like yanked out of her garden. For crying out loud. Sure enough. Those wee four-leafed starters from last year turned into thigh-high big bursts of vivid color: clear red, pink, deep fuschia. The scent is a bit like oregano, strong and –– allegedly –– unappealing to some of the hungry natives of the Would-Be. I don't know if deer and rabbits and porcupine and woodchucks and all will continue to avoid the plantings. It's all one big experiment. I've put tasty fruit trees in the midst of all that color, hiding them among the strong scent and bright color until they are tall enough to avoid the predators themselves. Meanwhile, call them bee balm or Monarda, them what you will, the flowerbeds are hugely popular with the pollinators We'll see if they take over the orchard. We'll see if they protect fruit trees. Knock wood, we'll see.

Oh glory! Back in 2019, my sweet mother-in-law Pat and I spent a delightful weekend planting jonquil bulbs.

*Little known fact: Squirrels cherish lofty landscape architecture ambitions. Unsupported by taste or formal learning, but marked by passion and energy. And then the waiting begins. A winter passes. The first spring arrives, and the bulbs do their job, transforming stored potential energy into cheer. Any chunky little bit of starch can tide a body through a season. No judgement. We've all been there. Anyhow, the real test of the bulb comes after a full year. Has the little bulb put down roots? Have the squirrels decided to remodel the bed of flowers? So this spring? Hurrah. The bulbs have mostly flourished, putting up multiple stalks and lovely flowers.

In the nature of gardening nature, however, I find myself perusing those colorful catalogues for just a feeeeew more.

As a green lass, I also read A.E. Housman's The Loveliest of Trees. It's got the virtue of being short to balance against its general gloom and the inherent math problem of "threescore and ten." For those of us who don't calculate in base score, "threescore and ten" means 70, the average span of human life. His point is that 50 springs is not enough, no matter how you slice it. Preach it, brother.

I've over-ordered spring plantings, I've pack-ratted a mound of supplies, and as soon as I manage my second vaccination shot, we are heading to the Would-Be Farm. Because it's April. Already! It's a very good Scrabble day when I can play "jonquil." In the world, I rarely call these flowers anything but daffodils. Be that as it may, my sweet mother-in-law calls them jonquils, and when she proposed a big honking field of them at the Would-Be Farm, I said heck yeah! Pat is a wonderful gardener, and even in her early 80s, she can out-shop, out-weed, and out-sew me pretty much any day of the week. So when she said she wanted Jeff and me to be reminded of her each spring at the Would-Be Farm, I enlisted her actual aid. Long story short, we ordered something like 200 bulbs from Holland last fall. Thank you John Scheepers. We hopped a plane (back in the days when people did that kind of thing without thinking about it much) once the package arrived in the North Country. We made a girl's weekend of it, staying at my sister's civilized house, eating yummy meals, and playing dominoes at the end of the day. And we flew South, happy but full of anticipation and the usual worries: Would squirrels eat the bulbs? Would the plants freeze to death? Would deer eat the bulbs? Would an early thaw fool the plants?

Springtime is brutal on hopes. When bright flowers do indeed rise from the cold clay -- oh glory. They show up. How cool is that? I may have planted these columbines.

I might have planted them last year. They might have been growing for decades, regardless my interference or ambitions. One of the downsides of being an absentee farmer is that things happen –– and don't happen –– without our being there to witness it. Sometimes we do. "Chrysanthemum" comes from the Greek for "gold" and "flower." You know these flowers: big tidy pots of blooms that last for ages. They show up for sale in the front of high-end grocery stores and at the big hardware warehouse stores. Mums, as we call them in English. Mums at Halloween, autumn colors for Thanksgiving. In Australia, mums are the traditional flower for Mother's day. In China, they are the symbol of autumn and purity. The chrysanthemum is the official flower of Chicago. Who knew? In India, a girl wearing chrysanthemums in her hair is said to bring happiness to her family. And in Japan, they represent longevity. The royal family sits on the chrysanthemum throne. But also –– so I understand after reading one of the Sano Ichiru mysteries by Laura Joh Rowland –– it's a symbol of homosexuality in samurai times. Yeah, don't think about it. But in France, they are the flower for tombstones. People put them in the graveyard on All Saints. For years, I have mistakenly believed that Charles Baudelaire's famous book of poetry Les Fleurs du Mal –– a chunk of which I translated in college, for pity's sake –– was both "the flowers of evil" (a metaphor) and also an actual flower: chrysanthemums. Whenever I saw the cheerful round faces of chrysanthemums, my busy brain would supply the subtitle, "Les fleurs du mal!" But nope. Baudelaire anyhow wasn't referencing these particular flowers in his poems about the pursuit of novelty and erotic decadence. How odd: such an infinitesimal and utterly trivial prejudice against an innocent flower, but I have held it for decades. Of course, it's worth remembering that one might also translate the title of that book (which I don't recommend, btw, as fun reading) as "the flowers from evil, or from suffering." Or something. Anyhow. They are long-suffering and colorful blossoms, no matter what I've mistakenly held against them. References

https://www.teleflora.com/meaning-of-flowers/chrysanthemum http://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/mag/2003/02/02/stories/2003020200110400.htm https://www.gardeningchannel.com/top-flowers-for-indian-weddings/ http://www.cerisepress.com/04/10/four-translations-from-les-fleurs-du-mal-by-charles-baudelaire "Years ago," wheezed the oldster, arthritic knuckles whitening on the handle of the deluxe walker. "Years ago, artists had to use rubylith to separate each color for a color print." Honking into a worn handkerchief, the dusty wheezer raised watery eyes and continued. "Hours I spent over a drafting table, X-Acto blade in hand, separating colors. The eye-hand coordination alone --!" After a long pause, the lecture continued. "It took years to learn the tricks of the trade. Nowadays, all it takes is a ninety-nine cent app. Putting artists out of business. I don't know how they make a living any more." Yeah, artists mostly don't make a living. In honor of all of us antiquities who remember cutting ruby to separate colors, here's a timelapse video of the Rubylith process... But those 99-cent apps are really fun: In this highly digitized age, it's nigh on impossible to grasp the amount of work that went into, for instance, the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz. This link describes the Technicolor process.

Such an effort to give the viewing public ruby slippers!

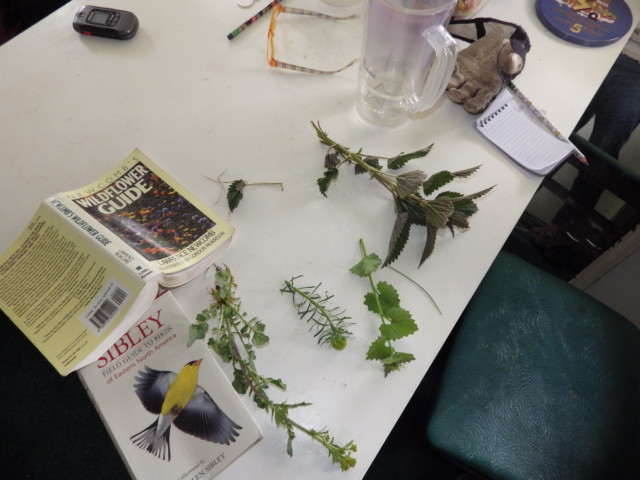

During the all-too-brief week we spent on the Would-Be Farm in early July, I decided to postpone the research by getting clear (clear-ish) photos of the latest crop of mystery plants. This is not rocket science, but I am only just skidding into the new century of digital memory. When I was a googly-eyed junior in high school, being all moony and swoony over my equally googly-eyed boyfriend, our biology teacher, Mr. V. would shake his head at the sight of us two and mutter under his breath, "Two smarts equal dummy." Oh, Mr. V., even just the one sometimes equals dummy! Here's a few of the unknowns: I figured I'd have tons to time to do the research during my months away from the farm. After all, some of these plants are bound to be edible. So far, not so much research, but the winter is still young...

We spend a good portion of our time, we humans, trying to identify and categorize all manner of creatures, including one another. (Is that a boy or a girl? What kind of accent/haircut/outfit is that? One of ours or one of theirs?)

And, even when we can't identify, we sort things as either "good" or "not-good." Any little kid can tell you that dolphins are nice and good, while sharks are mean and scary.

Anyhoo.

Judging is arguably how we survived for hundreds of thousands of years of evolution: correctly id-ing food vs. non-food, sorting bad guys from among the good folk of the world, drawing clever parallels between similar things.

"What's past is prologue"* even with as spendthrifty a pen (keyboard) as this one.

*This quote from of course, The Tempest. Act 2, with Antonio and Sebastian piffling away on shore. And with the prologue passed, the point of my piffle: While strolling through my tiny kingdom, I find myself not just trying to name the plants, but also sorting them by my lights as bad or good. I spent a studious half-hour or so on figuring out what these four plants were. Each with a maybe yellow flower, each growing rampant on the Would-Be Farm. Each a familiar mystery.

Right to left: the nettle is easy, but as it turns out, it's not common nettle, but Tall Nettle. The second is Garlic Mustard, then Cypress Spurge. And finally, with the dandelion-y leaves, Marsh Yellowcress.

Tall Nettle (Urtica procerea) is a stinger: tiny hairs on the stem will give you a dose of formic acid and histamine that feels a bit like the bite of a fire-ant. Dried, it's used to treat scalp problems, while traditional herbalists would suggest applying the stings to arthritic joints –– sometimes the cure is worse, wait, no, it does in fact work. Nettle also nutritious: steamed or cooked as spinach, nettle is full of Vitamin A and calcium. So while I want to say it's a bad plant, it's got its good points too. Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a garlic-scented member of the mustard family. Shocker, I know, with a name like that. Pretty solidly a baddie, although it's edible from top to toe. I will be grazing on this plant next spring, knock wood. Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias) is a recent (1860-ish) immigrant to the country. It's an ornamental that spreads rapidly. Its seed-pods detonate and can broadcast seeds up to five feet. Whoa. It's poisonous to horses and cows (but not sheep. Go figure.) While the milky sap is poisonous to humans, it has been used to remove warts. That's something. Cypress Spurge has some other traditional medicine uses, but I'm going to keep my gloves on and pull it as a weed. Marsh Yellowcress (Rorippa palustris) is a mustard and a cress, which is all to the good. It's native, it likes the boggy wetlands that stripe the farm, and it is edible raw (ooh! peppery!) or cooked (add a little olive oil and balsamic vinegar. nom nom nom). Is it ironic that I am basically re-discovering the common knowledge of my hunter-gatherer ancestors? |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed