|

Even if you didn't know the name –– a combination of "article" and "list" –– you've probably clicked through one of these short articles. They promise valuable content in a compact package, which seems ideal.

Formula? Take an integer + an over-the-top modifier and noun + a promise and Bob's your uncle. Like this:

27 Times Bacon Has Changed the Course of Modern History (Number 3 Will Make You Swear Off Eating in Restaurants!)

It's kind of addicting, actually, once you get going: 35 Things You Absolutely Need to Know about Roqueford Cheese

The numbers alone make me stop and think. I consider the cabalistic weight of them: are they prime numbers? is it whenever the data ran out?

And I wonder -– is it better to have 17 of the Most Adorable Hedgehog Videos or 13 of the Most Adorable Hedgehog Videos?

Trick question: There are not EVER enough adorable hedgehog videos in the world.

2 Comments

We spend a good portion of our time, we humans, trying to identify and categorize all manner of creatures, including one another. (Is that a boy or a girl? What kind of accent/haircut/outfit is that? One of ours or one of theirs?)

And, even when we can't identify, we sort things as either "good" or "not-good." Any little kid can tell you that dolphins are nice and good, while sharks are mean and scary.

Anyhoo.

Judging is arguably how we survived for hundreds of thousands of years of evolution: correctly id-ing food vs. non-food, sorting bad guys from among the good folk of the world, drawing clever parallels between similar things.

"What's past is prologue"* even with as spendthrifty a pen (keyboard) as this one.

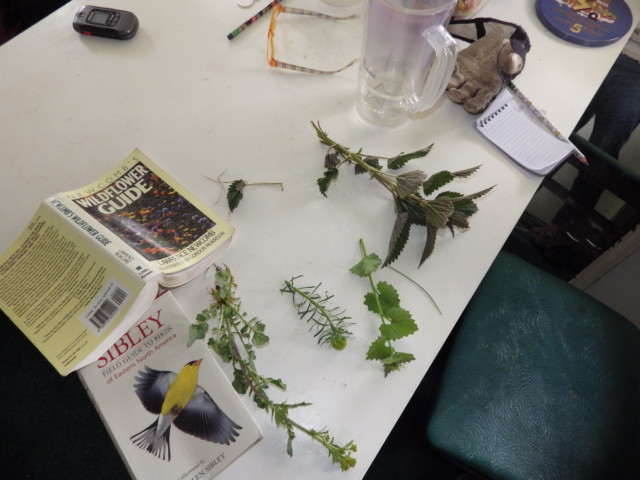

*This quote from of course, The Tempest. Act 2, with Antonio and Sebastian piffling away on shore. And with the prologue passed, the point of my piffle: While strolling through my tiny kingdom, I find myself not just trying to name the plants, but also sorting them by my lights as bad or good. I spent a studious half-hour or so on figuring out what these four plants were. Each with a maybe yellow flower, each growing rampant on the Would-Be Farm. Each a familiar mystery.

Right to left: the nettle is easy, but as it turns out, it's not common nettle, but Tall Nettle. The second is Garlic Mustard, then Cypress Spurge. And finally, with the dandelion-y leaves, Marsh Yellowcress.

Tall Nettle (Urtica procerea) is a stinger: tiny hairs on the stem will give you a dose of formic acid and histamine that feels a bit like the bite of a fire-ant. Dried, it's used to treat scalp problems, while traditional herbalists would suggest applying the stings to arthritic joints –– sometimes the cure is worse, wait, no, it does in fact work. Nettle also nutritious: steamed or cooked as spinach, nettle is full of Vitamin A and calcium. So while I want to say it's a bad plant, it's got its good points too. Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a garlic-scented member of the mustard family. Shocker, I know, with a name like that. Pretty solidly a baddie, although it's edible from top to toe. I will be grazing on this plant next spring, knock wood. Cypress Spurge (Euphorbia cyparissias) is a recent (1860-ish) immigrant to the country. It's an ornamental that spreads rapidly. Its seed-pods detonate and can broadcast seeds up to five feet. Whoa. It's poisonous to horses and cows (but not sheep. Go figure.) While the milky sap is poisonous to humans, it has been used to remove warts. That's something. Cypress Spurge has some other traditional medicine uses, but I'm going to keep my gloves on and pull it as a weed. Marsh Yellowcress (Rorippa palustris) is a mustard and a cress, which is all to the good. It's native, it likes the boggy wetlands that stripe the farm, and it is edible raw (ooh! peppery!) or cooked (add a little olive oil and balsamic vinegar. nom nom nom). Is it ironic that I am basically re-discovering the common knowledge of my hunter-gatherer ancestors?

We've been working on these apple trees of ours for three years now. We've planted new trees, but we've also thrown a lot of attention at the elderly groves we found long-neglected on the Would-Be farm. This year, there was undeniable progress: larger apples, happier apples, but alas...not-quite-ripe apples.

More were Tart like that nice little Mac that left an apple flavor behind after one spat out the pulp. It was possible to imagine that one day –– not far off –– that apple would be quite tasty. But not this day. Some were, we might say, Zippy. Too tart –– still apple-ish, but unpleasant. It's hard to imagine that this fruit will ripen. And Sour is only sour. No amount of wishful thinking can reverse the instantaneous prickling of sweat on the forehead after a nibble. Really sour. Mouth-shrinkingly sour. A hard bite of fruit that brings on a powerful thirst and the wish to wipe the flavor off one's tongue. And the most unhappy of fruits, which seemed frankly Inedible. These were dry, pithy samples that that tasted like lime and copper. As sour as a battery. Nasty-sour. Happy-to-let-the-wildlife-eat-it sour. Ah well. Another year without a satisfying harvest of apples. Farming is a long game, with a long learning curve, especially for part-timers. Too late one year, too early the next... one year we'll be on hand to enjoy the alchemy of those last few weeks of sunshine and cool nights turning sour green apples into something wonderful. PS. Okay, okay, one last dash of extra sensory-perception information: Music and taste. Can you taste music? This from Oxford U.  Hands down: Meg Rosoff"s The Bride's Farewell. Maybe the best book of my reading year. So many stories start off with a interesting set-up, but then turn in to the same-old same-old: An under-appreciated gal finds love and a glamorous makeover. The unreliable narrator turns out to be hiding a truth worse than you think at first. Square-jawed hero will decode the ages-old secret before the collapse of civilization. Freakishly clever serial killer will do awful things and then get caught, except he will escape in the last paragraph. Don't get me wrong, these books can be delightful. But we like surprises, we people do. Which might be why I have enjoyed this book so much. The Bride's Farewell starts with a girl running away from home the morning she's to wed. It's 1850-something, and Pell takes some food, the coins meant as her dowry, her beloved horse and, then, as she starts off, finds that her silent little brother, Bean, refuses to be left behind. Like many another character before her, Pell is different from her dirt-poor family, from other girls, from what society expects. It's not just her unwillingness to settle down and marry the local boy she's known her whole life. It's not just her fear of ending up like her mother, exhausted and wrung-out from endless childbearing and grinding disappointment. No, Pell is good with horses –– really good –– and she hopes to use this skill to make her own way through the world. But she does not quite reckon on the difficulties she'll face with people. The Bride's Farewell is full of surprises and twists that make perfect sense in hindsight (like all the best fiction). Pell's insight into the thoughts of animals (matched by her lack of insight into the thoughts of humans) is utterly convincing and thought-provoking. At 214 pages, it's easy to down in a single sitting, but Rosoff's stylistic strengths (the writing is vivid and restrained, with only the best details filled in) bear re-reading. Now go to your local and read it. "Chapter 2 The open road. What a trio of words. What a vision of blue sky and untouched hills and narrow trails heading God knew where and being free––free and hungry, free and cold, free and wet, free and lost. Who could mourn such conditions, faced with the alternative?"

But 11 is also pretty cool. It's a prime number (divisible only by itself and 1). But it's simply two ones standing together (it should be two, right? But it's not), which gives me the exact internal frisson of confusion that I feel while arriving at the airport and heading toward "Departures."

Anyway, cognitive dissonance aside, eleven elevens make 121, which seems mystical. Twenty-two of them is 242, while thirty-three of them is 363. Et cetera. The possibility of deep nerdishness exists around any topic. All this by way of introduction, really, to a couple of my favorite enthusiasts who dive into human perception of numbers (is 2 a masculine number or a feminine one?). Give yourself an hour of cool information and entertainment with Jad and Robert on this link to the...Radiolab podcast. Every spring on the Would-Be Farm, I go on rock safari. Not like it's a real challenge to locate stone –– the hilly landscape was created by glaciers and its only half a joke to say that the Farm's three most reliable crops are porcupines, burdocks, and rocks. But in the spring, small boulders appear as if by magic in the middle of the fields. It looks as if a bear has come along and pried chunks of granite from the ground. Maybe cranky from the long sleep? Perhaps searching for grubs? What if it's a mysterious ursine ritual feat of strength? And, not for nothing, they've got a problem with you people! But no, this is "frost heave" at work. A prosaic name for the kind of amazing thing that happens with sub-zero temperatures, wet clay soil, and rocks. As anyone who has ever left a bottle of beer in the freezer knows, liquids expand on the way to becoming solids. In clay soil, water tends to pool. A small bit water pooling between a rock and the soil around it will expand and widen the gap between rock and dirt. A cycle of thawing and freezing allows more water in, which widens the gap farther and farther until there is enough volume for ice to pop the rock (this one pictured about 45 pounds of lower-back discomfort) clean out of the ground. The field doesn't care where the stone lands. Grass grows up –– and the next thing you know, you're clanking into the chunk of granite with some surprisingly delicate part of a large and expensive piece of mowing machinery. Smart money says to relocate the thing before the grass hides it.

Enter the Bobcat. This summer's unexpectedly large project involved culverts and ditches (that thrilling tale to be told another time) and rental equipment. Because the cost of a week's rental is the same as four days, we ended up with a small diesel Bobcat for a week. Only a couple of frost-heaved (frost-hove?) rocks appeared over this past winter, but the rockiness of the Farm seems nearly endless. At least four outcroppings of pink granite lurk around Base Camp, just waiting to catch a blade on the weed-whacker or trip a distracted walker. After attending to the thrilling culvert and ditch issues, we still had a few days custody of the equipment. Rock safari went into a higher gear: we cleared the rocky path to both old orchards, we dug up inconvenient boulders, we nudged large stones into more desirable spots. We both learned that operating a mini-excavator is as mesmerizing and addicting as any video game. Only when you look up, there's a wall, or a set of stairs, or something that will be scenic in a season or two.

The impulse that sent a person up a ladder or onto her friend's shoulders to make these amendments –– it makes me smile and feel a little more hopeful about the world we share. The decision to scratch a pair of wings onto a road-sign is a small, subversive act of humor and –– I believe –– genuine love. An act with no particular spiritual agenda aside from cheering up the next person who happens to notice. It's generous, random, and clever. Thank you, artists. Alternate interpretation: these are personal messages from the universe. As some of my spiritual friends will doubtless point out that once you start noticing, you'll see angels everywhere. Spinning in infinity, in the architecture, dancing on the heads of pins. Agreed...but pariodolia. Creative writing teacher Terra Pressler used to tell us to consciously look for visual miracles. Keeping my eyes open, I have seen a nightjar sleeping on a traffic light, a skywritten smiley-face over Tampa, and pale green lichen growing in the shape of an angel.

Some things I have learned about growing mushrooms: fungi digest their meals before ingesting them. Freaky deaky. It goes like this: fungus grows in a colony. A colony (the parts you don't see, usually) sends out cells that figure out what's for dinner. The fungus produces the appropriate enzymes and sweats these compounds into their general area. Complicated carbohydrates (wood, leaf-litter, manure, coffee grounds, old clothes) get broken into smaller components and then yum-yum-yum, the non-plant absorbs basic building blocks of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and so forth, transforming material into delicious meals for themselves. Most of this happens under the surface of stuff. When a log gets punky and papery, for instance, it's probably because fungi has colonized and mostly digested the good stuff from it. The part of the fungi that we do see? The odd grey growths on the sides of dead trees, the circles of orange toadstools, the package of vaguely phallic objects in the produce section of a grocery store? These caps and stems are the final stage of growth for some fungi. When fungi produce mushrooms, it's called "fruiting." And such fruit!

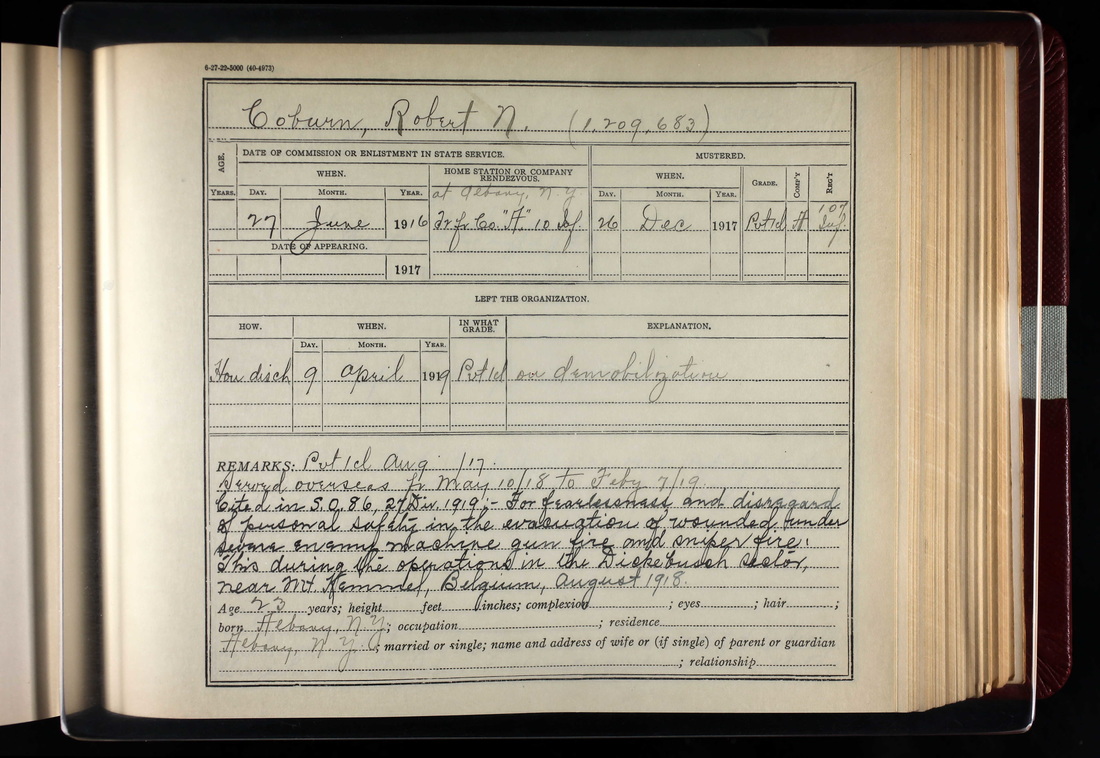

Varieties are blue or tan or yellow, tiiineensie or largo, spiky or smooth. Something edible for everyone: Shiitake, oyster mushrooms, portobellos, truffles, morels, hen-of-the-woods, maitake, lion's mane, nameko, blewit, wood-ear, enoki, blacktop, shaggy mane, tiger sawgill, scaly lentinus, hairy panus, turkey tail, king stropharia, parasol, elm oyster, the choices are legion. Me, I am not a fan. As my mother said of meatloaf: "Everyone has her own recipe, but it all tastes the same." Still, other people enjoy mushrooms. They buy them and everything. And as it happens, mushrooms might be another one of the crops that might thrive without a constant gardener looking after it. So that's part of our new neural pathway this spring at the Would-Be Farm: mushroom cultivation. I look forward to reporting details when we've accomplished something. New neural pathways, curiosity, adventure, exploration –– all kind of the same thing, right? Family stories are big in my family, but researching them has been fascinating to me lately. I vaguely remember my grandmother Mimi talking about her uncle the soldier –– how maybe he came back from the Great War a bit shaky and how her father (the real-estate guy who used to embarrass her so by yanking up his pant-leg to show off his snake-bite scar when her friends were visiting!) got him set up in real estate...but I don't remember hearing that Uncle Robert Coburn was decorated for retrieving wounded fellow soldiers in that war under heavy machine-gun fire. Huh.

Another entry in the series of stopping and reflecting on what's wonderful in my corner of the world.

|

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed