My sister assures me that genealogy is absolutely, supremely, and irredeemably dull. Unless you are doing the research, it's BORING. She doesn't sugar-coat it. Yet even she was willing to admit that great-great uncle Aaron Augustus Chase* was actually kind of inspiring. Bit of background: In 1871, coal miners in Scranton, Pennsylvania were protesting. The local coal companies had cut wages from $1.31 to $0.86 per car-load of coal in late 1870. The miners joined the Miners' and Laborers' Benevolent Association, which called for a strike. That strike subsequently began January 1871. On May 17, 1871, there was a large crowd of strikers (and their family members) protesting the scab laborers who were working the Brigg's shaft in the Scranton neighborhood of Hyde Park. As reported in History of Scranton and its People by Col. Frederick L. Hitchcock, published in 1914. the protesting included "jeers, hootings, vile names and threatening gestures as the men went to and from the mine." (ooh! hurtful hootings!) "Opprobrious epithets" were flung. And then perhaps a stone took to the air, which lead like night follows day, to an escallation of violence. Two strikers, Benjamin Davis and Daniel Jones, were killed by a single shot from the squad of militia hired by Mr. W. W. Scranton, superintendent of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company to guard the workers. Enter Aaron Augustus Chase. The editor of the Scranton Times, he called out W. W. Scranton and wrote that the killings of Davis and Jones amounted to murder. He ended up in prison twice, but refused to retract the statement. Yes, he was a Civil War veteran, which probably means he was a hero already, and his later life included a stint as judge and civil servant for the City of Scranton –– the town named for the family of the industrialist whom he called responsible for murder. But moral conviction and action in the interest of downtrodden workers? It warms the cockles of my heart. *Aaaron Augustus was my great-great-great-great-grandfather's cousin, but seriously –– in the interest of a story, I am thinking he's an uncle. PS. The Long Strike of 1871 was not, of course, the end of the labor troubles. The Great Strike of 1877 nearly shut down the country, and in 1891, 19 unarmed immigrant miners were killed in Lattimer, PA. And on and on. As Kurt Vonnegut said, "So it goes."

4 Comments

There are many things I don't know, but economic history is close to the farthest edge of my solar system. (In strict honesty, let me admit that I also didn't know that Louis Sherry sold more than chocolate and ice-cream, and those things circle my sun pretty closely.) Luckily, Mary not only has a PhD in the topic, she is an impassioned and delightful storyteller. To paraphrase (and probably confabulate some details), it goes something like this:

The good news for the country's eventual financial stability is that this panic led pretty smartly to the foundation of the Federal Reserve System. And even I know that the Fed is the central bank that sets interest rates and money reserves and government securities.

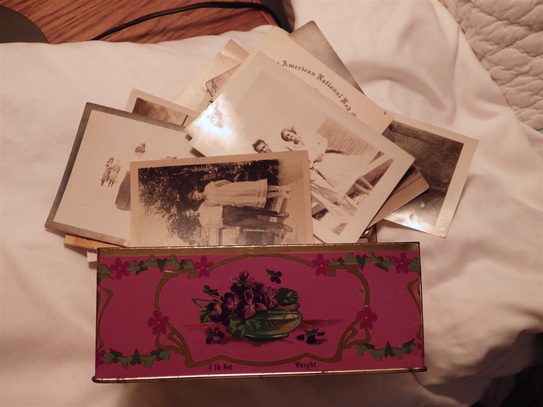

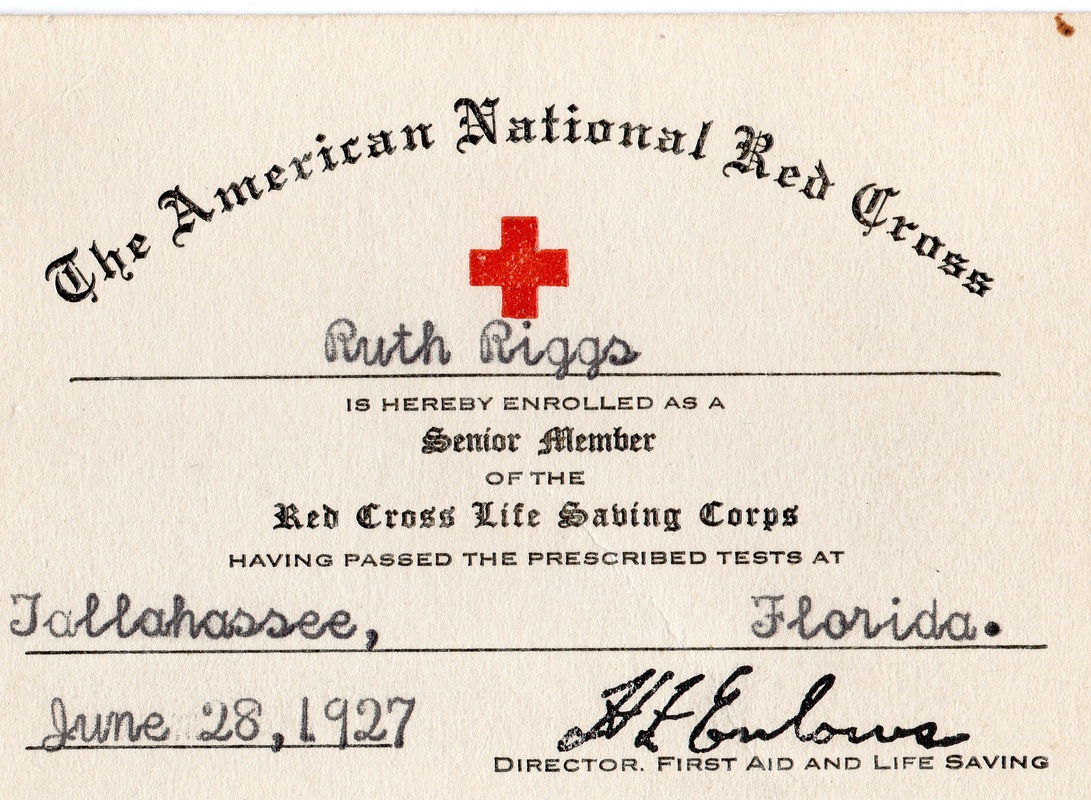

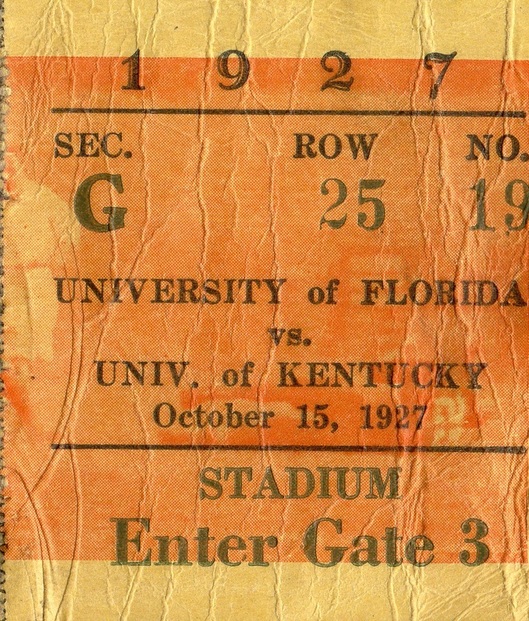

A quick poke around the interwebs shows me that Louis Sherry's was one of the most exclusive restaurants in those halcyon New York years before the first World War. In the same stratum as Waldorf's and Delmonico's. There was even a very deluxe 5th Avenue building for the restaurant, designed by the Sanford White (he of Girl in a Red Velvet Swing and Ragtime fame). After Prohibition and the rise of Bolshie waiters who just wouldn't do the work, these fabulous New York eateries faded or geared down. Louis Sherry himself turned back to his confectionary shop, which makes chocolates even now. Ephemera: items of fleeting use, or lasting a single day. A single item would be called an ephemeron. In the course of history, "ephemera" has described a fever (perhaps a 24-hour bug) and actual insects like mayflies. But at present, ephemera usually refers to the scraps of paper that show a glimpse into the specific past. Like my grandmother's Red Cross Life Saving Corps certification card: And this a ticket stub: Which give a little color to this snapshot of Ruthie: Ninety years of fleeting days since she was a kid at college with her life a big unknown ahead of her.

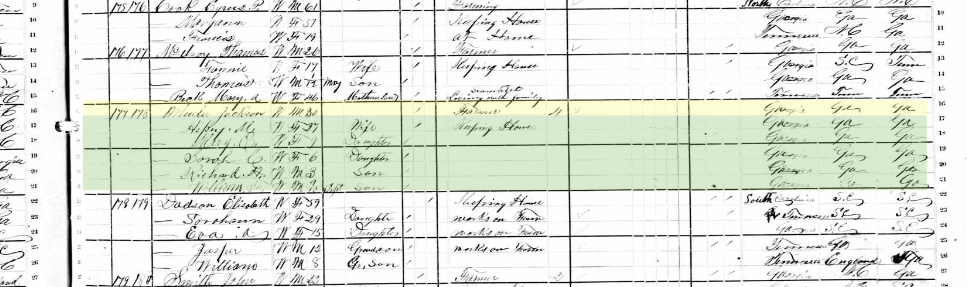

Once upon a time I was rich in grandparents. My trove included five full sets of grandparents hale and hearty up until my middle-school years or so. They multiplied by virtue of divorce (in the 1950s! quelle scandal!) and re-marriages, plus a slightly confusing second marriage that joined a pair of in-law great-grandparents. Mimi's mom married Bompa's dad? Wha--? I had ten grandparents, most in town and ready to babysit. They told stories about their parents and their parents, about dogs they'd loved, and horses that pulled the wagon even when the driver was tipsy. Snake bites and clairvoyance, kidnaps and practical jokes, consumptives and stowaways, scalawags and underage soldiers, and a cousin of Mamie Eisenhower. No wonder I'm interested in where they came from. Those storytellers have passed beyond the stage-curtains now, leaving behind metal boxes of snapshots and documents. Still interested, I've been shuffling through the short stack of notes in various handwritings –– how strange it is that my grandfather Bompa and I make the same neat humped m's –– about family history. Enter Hepzepia Elizabeth Vaughn. The iron-willed grandmother of my Granpa Navy who raised a family alone after her husband Russell –– one of the scalawag rascals –– lit out for parts unknown. With a name like that, she should have been one of the easiest people to research: a rock amid the flood of Marys and Ellens and Earls and Charleses. Ten years of idle pasttime research and no Hepzepia in the right time or place. No Vaughns. Not even a hint of rascally Russel. And then, like a stubborn padlock finally opening on the hasp, I found this in the 1880 Federal census: The right timeframe, the correct county, the right names and ages for the youngsters, but Hessy? Married to Jackson.

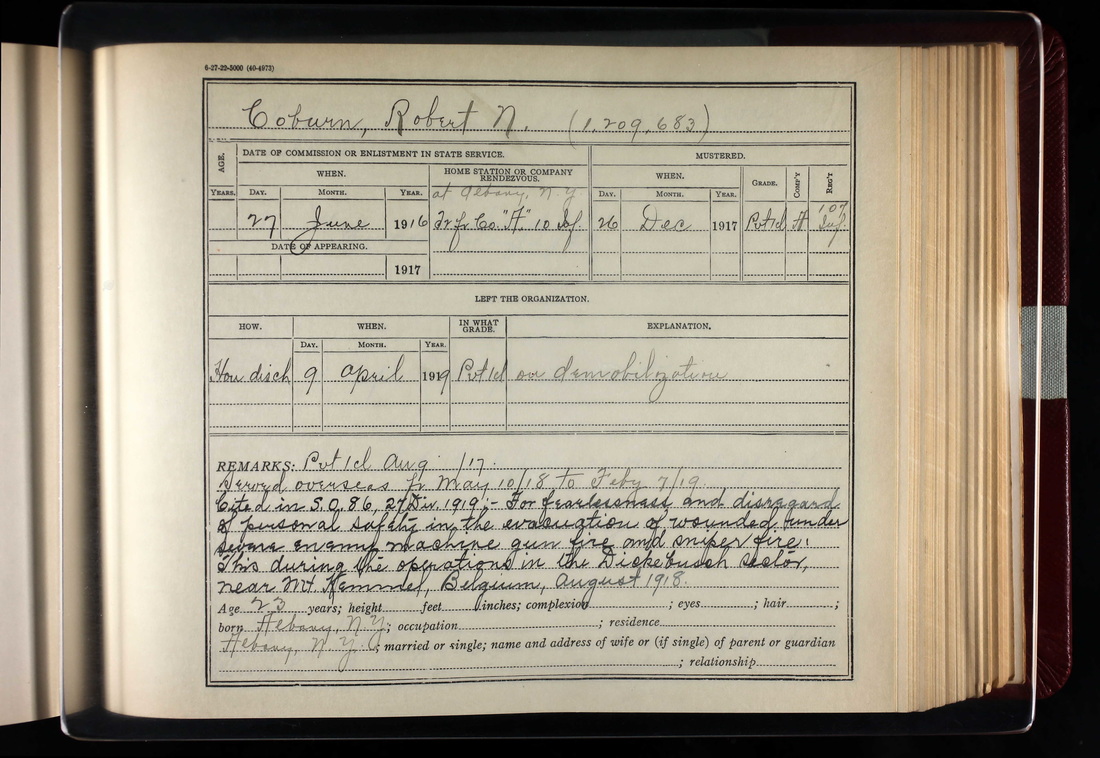

Imagine stern grandmother Hepzepia as a young woman, keeping home with a handful of kids. Perhaps she was light-hearted. Possibly in love. Maybe her husband (a first husband? A good-hearted brother to awful Russel?) answering the census-taker's question, filled in his pet name for her. The census-taker, dipping his pen in the traveling inkwell, taking a stab at the spelling. Click click click, another few hours, and here's what I find out: Russel often used his middle name on official forms, as Russel Jackson, or RJ or R. Jackson. And on her death certificate (cancer of the bowel and stomach –– no wonder she seemed stern), there it is: Hepsie Vaughter. Not Hepzepia at all. She was Hepsie, a rhyme with Pepsi. Imagine that. New neural pathways, curiosity, adventure, exploration –– all kind of the same thing, right? Family stories are big in my family, but researching them has been fascinating to me lately. I vaguely remember my grandmother Mimi talking about her uncle the soldier –– how maybe he came back from the Great War a bit shaky and how her father (the real-estate guy who used to embarrass her so by yanking up his pant-leg to show off his snake-bite scar when her friends were visiting!) got him set up in real estate...but I don't remember hearing that Uncle Robert Coburn was decorated for retrieving wounded fellow soldiers in that war under heavy machine-gun fire. Huh.

The sacred roster of good dancers from high school, the horsey adventures with best-friend Sue, the thrill of getting her own first apartment and a sports-car -- I inherited these adventures from my mother. Like the bone-structure and the need for glasses. As well as this wordy impulse to turn incidents into epic.

I'm not alone in this one: after a radical re-arrangement of furniture, I found myself walking to where my clothes had been kept -- even though I knew with my rational brain that the chest-of-drawers had already been relocated to a different zip code.

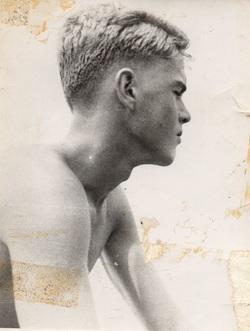

Despite understanding the whereabouts of my wardrobe, I could not give up the sense -- the conviction even -- that the clothing was still there. Day after day, I'd stomp into the empty room, reach into empty space and be shocked. And a few hours later, I'd do it all again. It was a piece of insight into how my grand-mother Mimi struggled in her later years. Having spent decades shuttling between summer and winter houses with the station-wagon loaded to the gills, she fixed on the idea of a specific set of blue dishes that she just KNEW were on the top shelf of a closet. She had hauled lamps and vases and pictures from one end to the other of her orbit of the Eastern Seaboard for years, but it was THIS set of dishes that gave her phantom pain. In those last few years, stopping by Mimi's meant climbing up into the closet and emptying the shelves for Mimi's disappointed inspection. Sometimes twice on a visit. She never stopped believing, I think, even despite every evidence of her senses, that those blue dishes were up there there on that shelf. Maybe in some parallel universe they still are. Where else could they be?  He was tall, dark, and handsome, my father. Rangy as the Marlboro man, he had straight teeth and good bone-structure. Brown eyes and a tan the color of mahogany. He rocked the Ray-Bay aviators and a cigarette. He played piano by ear and slowly wrecked his elegant hands with rough carpentry and masonry work. In photos he looks like a movie star, equal parts James Dean and Clint Eastwood. So many things to remember -- little quirks and big adventures, his imagination and creativity, his lifelong friendships, the oddball vocabulary and phrases. There was a theatricality about him: upon opening a beer and taking the first sip, he'd say, "How do they make it taste so good?"  A nap? Well, "A rested hand is a steady hand." During a card-game, he reacted to anyone's belly-aching by painstakingly retrieving a quarter from his pocket and then sliding it deliberately across the table, and saying -- with a certain restrained malice -- "Here you go, why don't you call someone who gives a damn." Before dry-swallowing an aspirin, he'd look into his palm and say with wonderful puzzlement, "How do it know?" Daddo offered dramatic, matinée-idol advice with a cigarette in one hand and a beer in the other, "Develop many interests, honey," he'd say. "Because one by one --" Pause for a sip and a deep breath of smoke, and the rest of the line delivered with absolute sincerity, "You'll be forced to give them up." "Do it right or do it twice," was his carpentering advice, sometimes inverted as, "Anything worth doing is worth doing right." His workshop was a wonder of neatness.

On the job site, he once called out, "Uh, honey?" from the other room, where he was replacing a ceiling fan while I rolled paint. "Honey, REAL painters don't say 'oopsie.' " Fifteen years and whenever the word comes out, I remind myself each and every time that real painters (real dish-washers, real gardeners, real parallel-parkers, real basketball shooters, real anything-ers) don't say "oopsie." |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed