This ties into my New Year's genealogy binge. My binge was marked by long stints in front of the trusty laptop punctuated by exclamations of, "Huh. Well of course it's his great-uncle Gorton," and "What were the chances that these two families would intermarry this many times? Jeesh. Guess they swiped right on KINder. Nyuk nyuk nyuk."

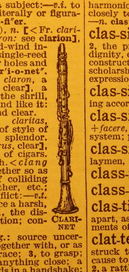

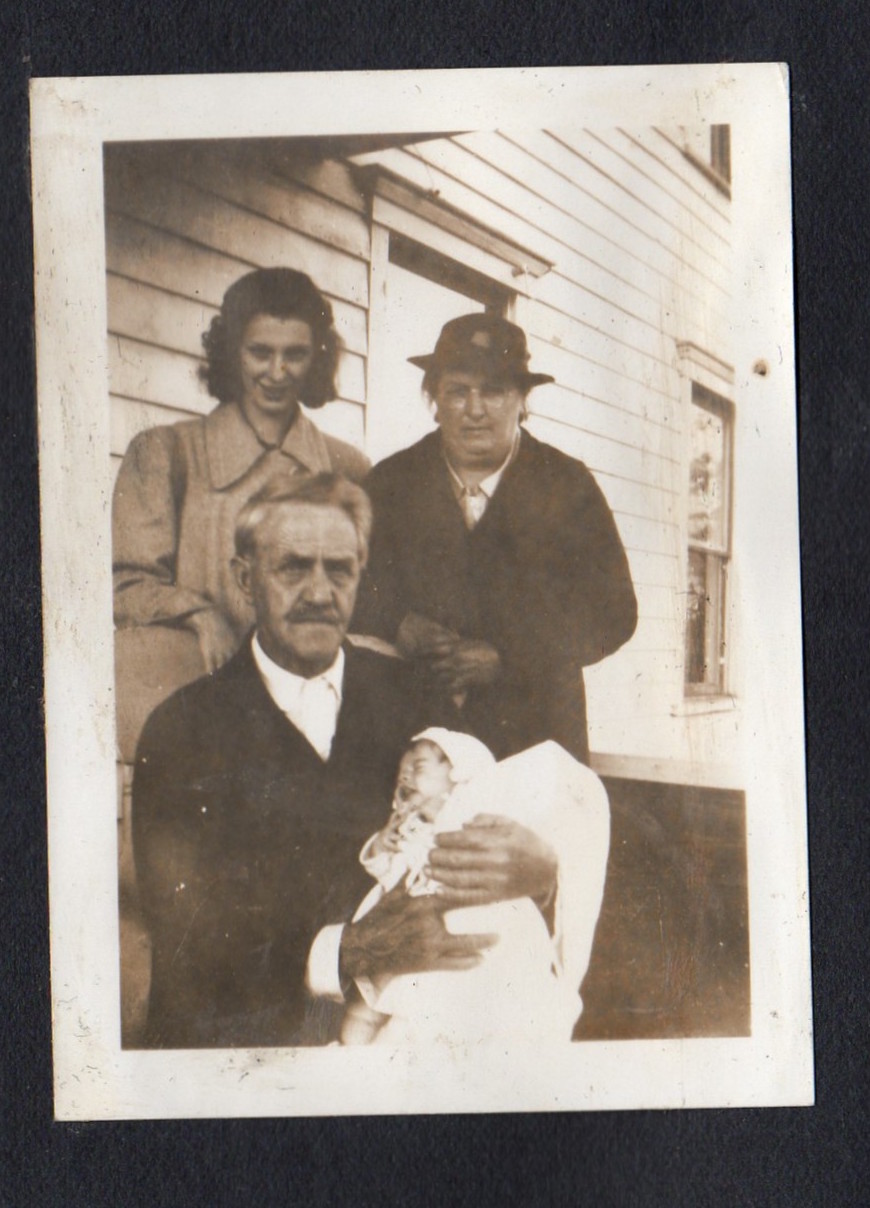

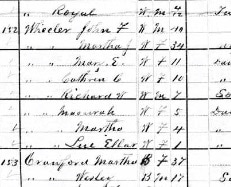

But back to my binge: I was poking into the history of my Wheeler kin. They lived way up in the hills of Franklin County, Georgia, fifty or so miles southwest of Asheville, NC. My Grampa Navy would have pronounced that word as "he-ills." Franklin County held quite a number of likely Richard Wheelers who might be my great-great-grandfather, but he's been a sticky wicket. In that steep corner of the world, Wheelers bifurcated like tadpoles in a pond. And they each named their kids after the same uncles and dads: William, Richard, John, James.

Taking a closer look at the census-taker’s handwriting, I saw that Lu Ellar is more likely “Sue Ellen.” Regional –– but not so over-the-top as "Lu-Ellar."

Mr. Foreman used to insist that we pronounce the lyrics as befitted the song and its historical setting (just as a later professor taught me to read Spenser so that it rhymed). So when the chorus came up in my mind (and –– full disclosure –– throughout the living room) I sang it this way: “A-WAY! I’m bound away, across the wide Missor-ah.”

If Lu Ellar can be Sue Ellen, what about Massurah? Massurah, Missourah...Missouri. Missouri? Click-click-click and it turns out that Massurah was the delightfully easier-to-track Missouri Caroline Wheeler. Her grandfather was my great-great-great grandfather. I don’t yet know why she was given this unusual name, but I do have a better handle on Richard, son of Mary Freeman and William Wheeler.

2 Comments

Laura

1/18/2017 11:48:55 am

I remember Mr. Foreman! Cool story.

Reply

Amy

1/19/2017 03:21:16 pm

Thank you, Laura. Did you have music lessons with him too?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Blog

A lot of ground gets covered on this blog -- from sailboat racing to book suggestions to plain old piffle. FollowTrying to keep track? Follow me on Facebook or Twitter or if you use an aggregator, click the RSS option below.

Old school? Sign up for the newsletter and I'll shoot you a short e-mail when there's something new.

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed